Saquib Salim

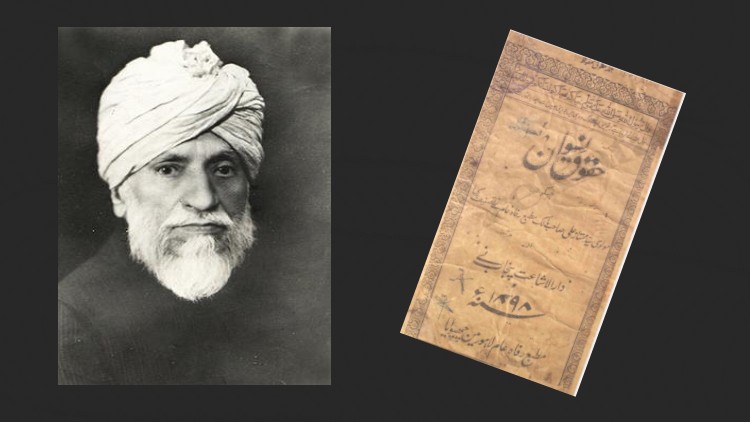

Maulvi Sayyid Mumtaz Ali, at some time in 1890s, visited Aligarh to show Sir Syed Ahmad Khan the manuscript of a book he had written. As Sir Syed started reading it, his shock was visible and after shuffling through a few pages. He was frowning. He asked Mumtaz, much younger to him, what kind of trash was this and tore the manuscript down. Mumtaz later collected the mutilated manuscript from the trash and published it only a few months after the death of Sir Syed in 1898.

What was there in the book that infuriated Sir Syed?

The book was Huquq un-Niswan (Rights of Women), a treatise advocating rights of women under Islamic laws. Sayyid Mumtaz Ali, who studied at Deoband along with Sheikh-ul-Hind Mahmud al-Hasan, was of a view that the women in Islam had equal rights as that of men and the inferior position they were in owed to the false customs in the society. Therefore, it was necessary to educate men and women of the legal rights of women in Islam based upon authentic Quranic interpretations and traditions of Hadith.

The book was so revolutionary for its time that even a modern educationist like Sir Syed Ahmad Khan was afraid to accept its arguments.

In the introduction of the book, Mumtaz foresaw that the people would call him an English man, or a Christian agent. He believed that anyone having knowledge of the Quran and Hadith, and respect for the Prophet and his family would accept his arguments to shun the un-Islamic practice of treating women inferior.

The book was broadly divided into five parts; false social construct of believing men to be superior to women; education of women; Purdah system (veil); marriage; relationship of husband and wife.

Logical approach

Mumtaz has adopted the approach of a polemicist, where he first lists the arguments prevalent in the society and then counters them with verses of Quran, traditions of Hadith and logical interpretations. Though seemingly modern in its approach, the book keeps itself within the framework of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence in Islam.

While it is out of the scope of this article to summarise all the arguments contained in the book, I will still try to discuss a few of his important arguments to give readers an idea of how revolutionary the text was even by today’s standards.

First of all while countering the argument that men are made superior to women by Allah because men have been granted the greater physical strength, Mumtaz argues that a donkey has more physical strength than a man so does it make a donkey superior to man. Humans are superior to animals because of wisdom and not physical strength. Allah has not made women any less in wisdom.

He further counters the argument that women are spiritually inferior and no woman has ever been made a prophet by saying that the names of only a few among 1,25,000 prophets are known, surely none of the known is a woman but nowhere in Quran or Hadith it is specified that none among the unknown can be a woman.

Breaks myth with reason

It is highly possible that there are women among the prophets whose names are unknown. Moreover, though humans can claim a spiritual superiority over animals, between men and women there cannot be such a distinction. There can be men who are spiritually superior to other men and women and similarly women can be spiritually superior to men and women. To prove his point, he invokes the examples of Hazrat Fatima, the daughter of Prophet Muhammad, and mystic poet Rabia Basri.

Mumtaz completely dismisses the belief that Allah has created Eve after Adam to provide him a companion. In his view a counter argument, that Allah who knows everything, past, present and future, perfectly knew that He is going to make Eve, therefore in order keep her a company Adam was made before Eve, is more plausible.

Mumtaz goes on to argue that since Allah has made it obligatory on every Muslim to gain knowledge without any distinction of gender therefore women should be educated in the same manner as men are.

People who say that a certain kind of education or books are not fit for women should understand that if a book is dangerous for society then it is for both the genders and not for women alone. In his view, it is a religious duty to educate women in the same manner as men are being taught.

On Purdah and modesty

On purdah, Mumtaz argues that the Quranic verse about modesty which asks believers to cast their eyes down and cover their private parts is applicable to men and women equally. Another verse, which asks women to cover breasts is part of modest clothing and does not disable women in their social and economic lives.

In the Quran, when women are asked not to go everywhere like in pre-Islamic times it again does not ask them to remain inside homes every time. To cut it short, he argues with a number of Hadith and Quranic verses that women are allowed to keep their faces and hands open. Moreover there is no Islamic ruling that women cannot step outside homes, a common practice of those times.

Mumtaz discourages early marriage on account that in Islam man and woman are supposed to give consent for marraige. So, they should be of the age where they understand what is at the stake. He further argues that early pregnancy is also not in line with the Islamic teachings. In the book he argues against the dowry and extravagant wedding ceremonies as well.

Mumtaz, in the book, provides solutions to the social ill by opening schools and printing journals for women.

Revolutionary text

The text seems revolutionary even by the present standards of Indian Muslims society and Mumtaz was writing around 125 years ago. No wonder, people criticised him and after printing the initial 1,000 copies the book never got into print again. Many people, to whom Mumtaz sent free copies of the book, returned it with letters full of abuses for him. As we move forward in time, we should look back at Mumtaz for inspiration.