Sabir Hussain/New Delhi

At 64, Shafat Ali Khan is India’s most sought-after hunter to put down rouge wild animals when they turn dangerous for humans.

The scion of an aristocratic family from Hyderabad, Khan lives most of the time in the Mudumalai National Park spread across the Nilgiri hills Tamil Nadu where he also runs a few resorts. Four decades of tracking and eliminating man-eating tigers and leopards, rogue elephants, wild boars, and nilgai (blue bulls) have turned him into a wildlife expert with an uncanny ability to size up an animal from telltale signs.

“I have been living here for decades. When I go out on my morning walk, I can often see a tiger or an elephant. Even if I don’t come across one, I can tell from pug marks whether it is a tiger or a tigress and from an elephant’s footprint I can tell the height of the elephant,” Khan told Awaz-The Voice.

Given the family’s background, he took to shikar, or hunting for sport, in the Nilgiri Hills like a duck takes to water.

“In those days hunting was legal. My grandfather Nawab Sultan Ali Khan Bahadur was a hunter and an advisor on wildlife to the British administration and I grew up in a house where there were many guns and trips to the jungle were frequent and dinner conversations were often stories of shikar. I became familiar with the forest and wild animals from an early age,” he says.

At the age of five, he won a prize in rifle shooting. He earned his spurs as a 19-year-old when shot a rogue elephant in Mysore in 1976.

“The Forest Department asked me to eliminate the elephant that had killed 12 people. After I killed the elephant, Khushwant Singh, who was then editor of the Illustrated Weekly of India, interviewed me, and almost overnight I became a celebrity of sorts.”

Amid rising man-animal conflict in India, many state governments turn to Khan as a last resort to put down man-eating tigers, leopards, and rogue elephants. And Khan is proud of his track record.

Shafath Ali Khan with a man-eating leopard he shot in Thunag, Himachal Pradesh in 2013.

Shafath Ali Khan with a man-eating leopard he shot in Thunag, Himachal Pradesh in 2013.

“I have 40 operations to my credit. And I have never shot a wrong animal. I am an advisor to forest departments several governments on wildlife management and managing man-animal conflict.”

He believes that the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 did not take a holistic view of wildlife and its management when it was formulated and its shortcomings have now aggravated the man-animal conflict.

“Before privy purse was abolished for India’s former royals, they were in charge of the forests in their land. Although many of them hunted for sport, they also cared about conservation that maintained the prey-predator balance. But after 1972 when the Wildlife Protection Act banned all types of hunting, the population of some species simply exploded. For example, the nilgai population is now a threat to farmers in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Gujarat, and wild boars are now vermin,” he says.

“The Wildlife Protection Act focused on conserving wildlife but did not focus on increasing forest cover and prey base. And since animals like tigers are territorial by nature, they come in conflict with humans when their territories shrink or prey diminishes. You can put 500 people in a high-rise building but you can’t put animals in small areas because they need large spaces.”

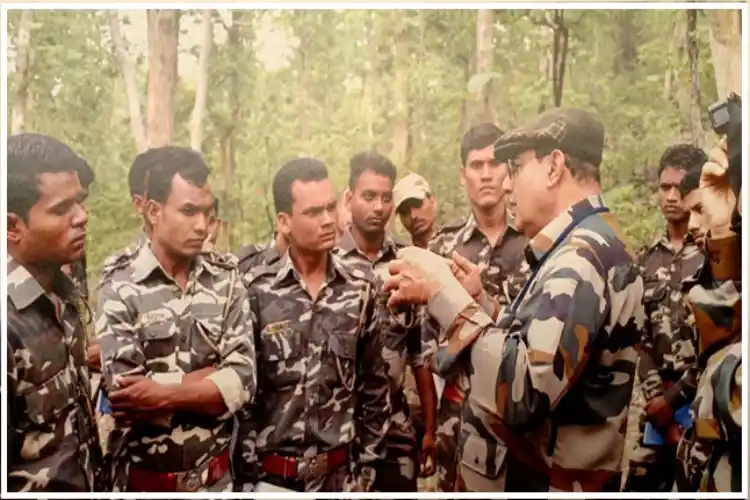

Nawab Shafath Ali Khan is an advisor to forest departments of several state governments.

Nawab Shafath Ali Khan is an advisor to forest departments of several state governments.

Unlike many other countries where culling is allowed to control wildlife population to maintain balance, it is not the case in India except for nilgais and wild boars.

“Hunting is allowed in many countries and local stakeholders benefit from it. But in India, the total ban on hunting has affected 5 crore people in 1.87 lakh villages for whom wildlife suddenly has no value. Compensation seldom comes if their crops are damaged or they are killed by animals. The number of elephants in India in 1987 was 18,000 which has now increased to 32,000. There is simply no space.”

He has no doubt that “conservation has gone haywire and made people enemies of animals” because forest policies are being made by those “who have no idea about ground realities.”

India’s tiger population of about 3000 creates another problem because tigers are highly territorial and need large space. On average, a tiger kills once a week and a single tiger would need at least 52 large prey animals a year to survive. It is when the prey base declines that a tiger strays out of its territory, starts lifting cattle, comes in conflict with humans, and turns man-eater.

Nawab Shafath Ali Khan sees himself as a saviour of rural people from depredation of rogue animals.

Nawab Shafath Ali Khan sees himself as a saviour of rural people from depredation of rogue animals.

Shafath Ali Khan maintains that his job is a highly specialized one that requires identifying the animal properly and trying to capture it alive and if that is not possible, then, shoot it dead. Although he has also tranquilized tigers and other animals, he has been accused by NGOs of being trigger-happy. But he insists he is saving human lives.

“Whatever arguments NGOs may have the fact remains that I save human lives when I kill a man-eating tiger or leopard or rogue elephant. Most of the victims are poor villagers, usually the sole earning member of the family. Why should the people near a forest continue to suffer the attacks of a man-eater even when the government issues an order to kill it?”

He holds up the case of man-eating tigress Avni in Maharashtra’s Yavatmal as an example. The tigress had been declared a man-eater and the Maharashtra Forest Department had engaged Khan after the Supreme Court authorized an operation to tranquilize and trap it or put it down. His son Asghar who is also a sharpshooter accompanied him for the assignment.

Nawab Shafath Ali Khan and his son Asghar.

Nawab Shafath Ali Khan and his son Asghar.

That hunt in 2018 turned out to be a hugely controversial one.

“We were tracking Avni and were closing in on her when I received an urgent call from the Bihar government to attend a meeting to address the threat of rampaging nilgai herds to standing crops. When I left for the meeting, Asghar took over the operations.”

Khan says there were efforts to sabotage the operation and alleges that two veterinary doctors procured tiger urine without authorization from the Nagpur zoo and sprinkled it around the camera trap laid for Avni which agitated the tigress.

“It happened on November 2, 2018. There was a weekly market in Ralegaonnear the forest and Avni had been sighted several times that day and in the late evening attacked a scooterist who survived. When Asghar heard about it he reached the site along with a forest officer in an SUV. The forester fired a tranquilizer dart at Avni but she turned and charged at the vehicle when Asghar shot it at close range at 11.30 pm.”

While villagers celebrated the killing of Avni and felicitated the father and son duo, an activist moved the Supreme Court claiming that Avni was not a man-eater and was killed in a trophy hunt. The Supreme Court dismissed that petition.

Shafath Ali Khan is an extraordinary marksman.

Shafath Ali Khan is an extraordinary marksman.

So why do governments hire him to kill rouge animals when forest guards are also armed?

“The weapons that foresters use such as .303 rifle or self-loading rifles are designed for use against an average human weighing 60 kilos. To kill a rampaging tiger or a rogue elephant that can charge at you suddenly, you need special hunting rifles. And besides, I have decades of experience of tracking animals and I am familiar with animal behaviour and ways of the jungle and those are things that can’t be taught which is why governments seek my service.”

Khan’s weapons of choice are a .458 magnum rifle and a .470 double-barrel rifle. He says he does not charge any money to kill rogue animals.

“I am satisfied with the travel arrangements and the accommodation that the state governments provide during an assignment. My primary concern is to save human lives and it gives me no great pleasure to kill some magnificent animals,” he says.

Although each assignment has been unique in itself, Khan says the toughest was the shooting of a rogue elephant in Jharkhand in 2017 which had let loose a reign of terror for six months.

“The tusker had crossed over to Bihar, killed four people, and then returned to Jharkhand where it killed 11 more people. We tracked the animal to the Raj Mahal Hills in Sahibganj. One of our veterinarians tried to tranquilize it with a dart but it charged at us and I shot it in the head from less than 10 metres.”

Also Read: In Turtuk, a museum keeps alive scent of Balti culture

Nawab Shafath Ali Khan is the last of his kind from an era when big game hunting was legal. For now, he remains the top gun for many governments to end the reign of terror of a rogue animal.