On May 4, 1995, the five-year-old Mir Ummer was playing cricket with his neighbour’s children in Uri, a town in north Kashmir when he heard gunshots. Everyone abandoned the game and rushed out.

“I had no idea that my father had been shot,” he recalls, 30 years later. “I have a hazy idea of someone calling my dad’s name, and everyone rushing out towards the paddy fields.” Sometime later, Ummer was taken to the local tuck shop where he was given a packet of biscuits and a few toffees to distract him from the wails and mourning by men and women at home.

Mir Ummer’s father, Mohammad Ashraf Mir, was the Deputy Forest Conservator. He was returning from work at dusk and asked his driver to drop him at the roadside so that he could walk home through the paddy field to save time for the driver.

Militants shot him; his body lay on the edge of the paddy field right across his house.

Ummer is among hundreds of Kashmiri Muslims who are yearning for justice for their kin killed by terrorists. As per the directions of the J&K Government, police can relaunch an investigation into the assassination of his father.

On that day, apart from the pain of losing his father, everything changed for Ummer, his mother Dilshada Ashraf, a teacher, and two younger brothers.

Within three months, the family had to move out of their big house as they were vulnerable to more terrorist attacks. “We shifted to Sopore, A nearby town, and later Srinagar and lived in rented houses, in fear and anonymity.”

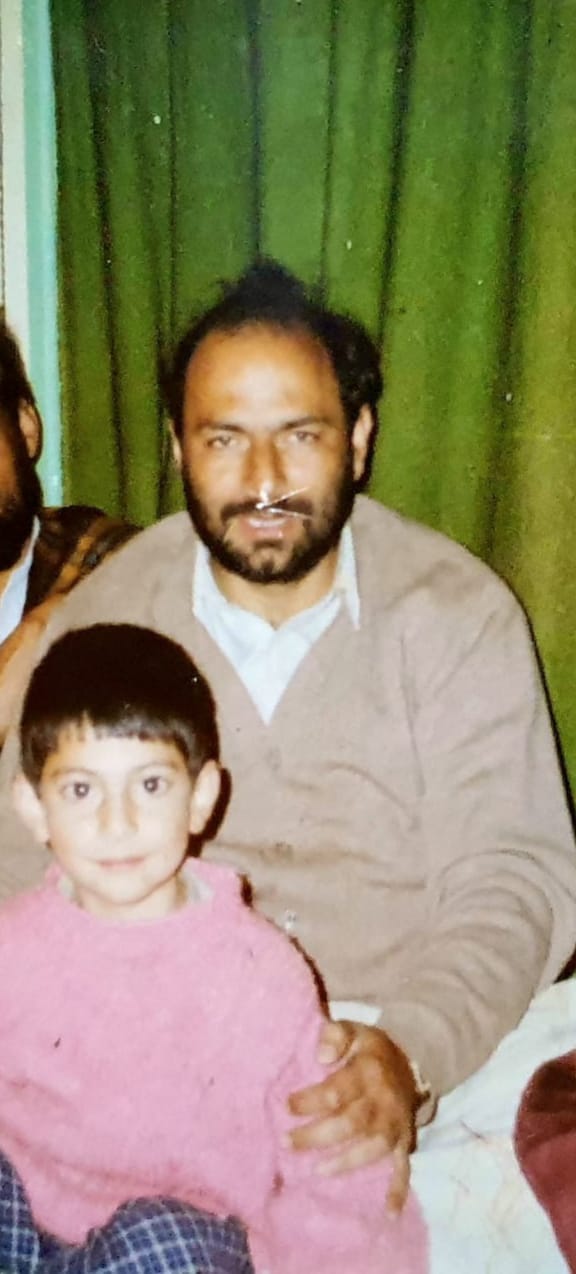

The little Ummer with his father

“We were cut off from our relatives and uprooted. It took a heavy toll on our minds." The relatives stopped interacting with them out of fear of the unknown, leaving a big emotional void in their lives.

From living in a house surrounded by 56-kanal land, Ummer and his family had to live in smaller houses and not reveal their full identities, for victims of terrorism were not seen with sympathy back then.

“The entire system was usurped by the pro-Pakistani elements. People like us – victims of militancy – had no patronage and support. We were made to feel guilty,” he told this reporter.

Ummer Mir has been teaching Constitution and governance to the USPC aspirants at various institutions for 11 years. He says the alienation took a heavy toll on his mother’s health as she suffered from mental depression and dementia. “She never went to the village where her matrimonial home and parents’ house were; she remained cut off from all her family while providing for us.”

Recently, taking advantage of the changed situation in Kashmir, Ummer returned to his ancestral house and asked for a share of the property from his uncles.

“I experienced how conflict is used by greedy humans; My uncles quoted Shariah (Islamic law) to explain that we have no right over the property.

“I know that this is not codified in Shariah or the Holy book. By my uncles' interpretation of Shariah, if a man dies leaving behind his minor children, they should be denied his property; Are they trying to throw the institution of marriage into the dustbin and treat minor children of a dead man as 'illegitimate?”

Ummer says that over the last six years, the ground situation in Kashmir has been changing fast, but the cobwebs of the past remain.

For example, while the Forest Department recently honoured its martyrs, including his father, and printed their pictures on the opening page of the Department's annual report, it failed to give a clear picture.

Instead of writing that terrorists killed these officers, the report said they were killed by "Unknown gunmen.

"Pakistan-backed militants killed my father, and even the FIR mentions the killers as "militants."

He objected to the misrepresentation of the facts, and the department stopped further circulation of the document.

"I raised questions. At least the government should speak the truth. We want our honour, land, and prestige back," Ummer said.

ALSO READ: After 30 years, Kashmir's forgotten terror victims to get justice