Pallab Bhattacharyya

Pallab BhattacharyyaThe geopolitical landscape often resembles a restless ocean, shifting with tides of opportunity and undercurrents of rivalry. For India, this dynamism is most vividly reflected in its ties with Bangladesh, China, and the wider world. The ouster of Sheikh Hasina on March 5 a leader who had shared a close understanding with New Delhi, sent tremors through bilateral relations. Yet, even amid this cooling of political warmth, India demonstrated pragmatism by resuming onion exports to Bangladesh, a modest 230 metric tonnes that carried a message far greater than their market value. It signalled that while governments may falter, the bonds between peoples must endure.

This approach of separating the transient from the permanent is becoming the fulcrum of India’s foreign policy. The tariff wars launched by Donald Trump during his presidency reminded India that great powers often wield trade as a weapon, forcing nations like ours to balance economic pragmatism with strategic autonomy. Nowhere is this delicate balancing act more apparent than in India’s complex, often turbulent, yet essential relationship with China.

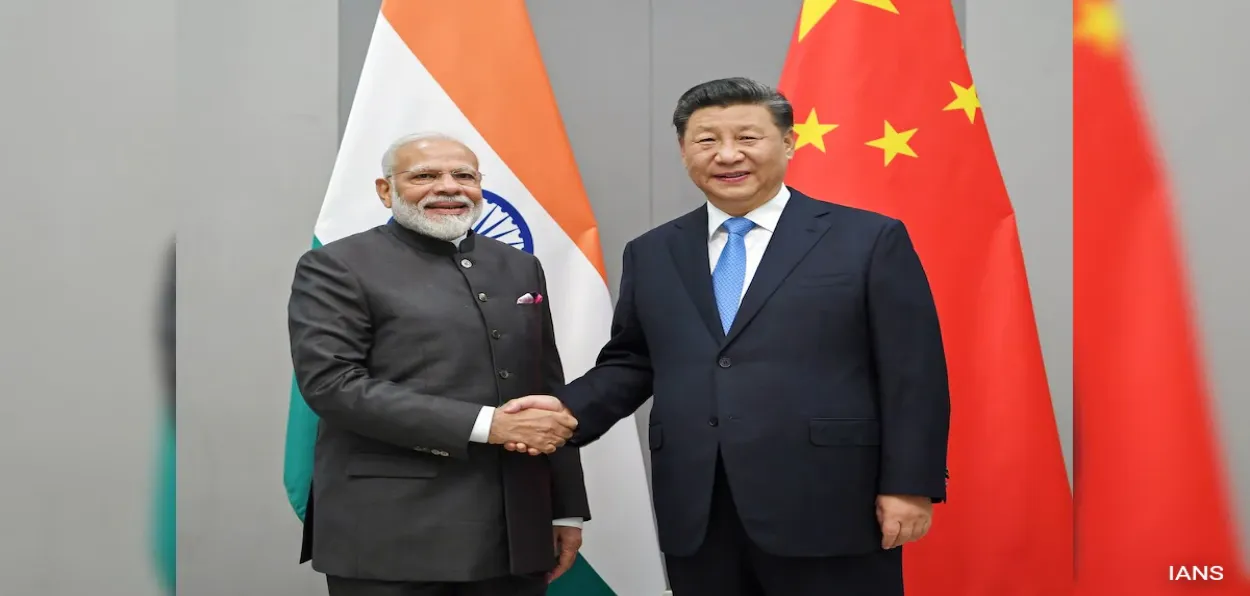

The two-day visit of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to New Delhi from August 18 after three years, marks a turning point. His discussions with National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar would lay the groundwork for Prime Minister Modi’s forthcoming visit to Tianjin for the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Summit—the first in seven years.

For two nations scarred by the memory of Galwan in 2020, the optics of renewed dialogue are as important as the substance. The elephant and the dragon, long wary of each other, are beginning once again to explore the possibility of walking side by side.

The thaw was not merely diplomatic. The resumption of direct flights, frozen since the pandemic and border clashes, symbolized an opening of skies and perhaps of hearts. The reopening of traditional border trade routes through Lipulekh, Shipki La, and Nathu La carried more cultural than commercial weight, yet in diplomacy, symbolism often carries the heaviest freight. Even India’s first diesel shipment to China since 2021 suggested that economics could carve pathways where politics hesitated.

No rapprochement comes without shadows. Tens of thousands of troops remain deployed along the Line of Actual Control, even as disengagement agreements soothe the surface. China’s infrastructural ambitions in Tibet and its steadfast embrace of Pakistan remain thorns in India’s side. Equally, India cannot ignore the nearly $100 billion trade deficit that tilts the scales of economic engagement. Thus, this renewed warmth must be viewed as tactical pragmatism rather than a full thaw.

Still, history teaches that even tactical realignments can change the course of nations. The shared pushback against Trump’s tariff diktats brought New Delhi and Beijing closer in resisting external pressure, proving that adversity can sometimes create unlikely alignments. From confrontation at Galwan to conversations in Delhi, the arc of India-China relations reflects both the fragility and resilience of international diplomacy.

Ultimately, the challenge for India is to move beyond the immediate three Ds of disengagement, de-escalation, and de-induction, and step toward a future shaped by three Cs—confidence, cooperation, and collaboration. For in an age when the world faces shared crises—climate change, pandemics, energy security—neither dragons nor elephants can afford to dance alone.

ALSO READ: Ayisha Abdul Basith shows how religion can empower one to rise in life

As Rabindranath Tagore once wrote, “You cannot cross the sea merely by standing and staring at the water.” For India and China, the choice is clear: to move forward together, cautiously but steadily, or to risk being trapped in the whirlpools of mistrust. The steps may be tentative, but the music of history is urging both to dance.