Saquib Salim

Saquib Salim

Where do you put Rana Safvi in a list of Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Rabindranath Tagore, VD Savarkar, Kishwar Naheed, and other revolutionary writers of the last century?

Book Review

Her latest translation, Tears of the Begums of Khwaja Hasan Nizami’s Urdu book Begumat ke Aansoo surely puts her into a tradition of writing nationalist history from a non-Eurocentric view and presenting it to a readership beyond vernacular.

Popular feminist Urdu poet Kishwar Naheed once wrote, “Our young people who understand English or other international languages well may consider learning Urdu and their mother tongues with as much fervour as they learn English or French and then translate the literary works of our languages into others.” Rana is living this dream of being one of the most well-known women poets from the subcontinent. She has previously translated, apart from authoring original works, Asar us Sanadid of Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan, an encyclopedia of a kind to the monuments of Delhi.

The translation of Begumat ke Aansoo puts her in a richer tradition of nationalist history writing as was envisioned by Maulana Abul Kalam Azad on becoming the first Education Minister of India. He believed that Indian history should be told by the Indians. At the inauguration of the Indian Historical Records Commission in 1950, he told a gathering of historians present, “It is, therefore, necessary that these records should be examined afresh, and a true account of the period written in as objective a manner as possible.”

Earlier, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay expressed a similar desire while writing, “When are we going to have our history? But, who will write it? You will write it, I will write it, everyone will write this history.”

Begumat ke Aansoo, published in the early 1920s, was the first account of the First War of Independence of 1857 through oral interviews. Today, it might seem a rather easy task of meeting, interviewing, and compiNG the accounts of the people who had survived one of the goriest episodes of the history of Delhi but at that time when writing in 1857 could land you in prison it was a huge service.

Nizami’s book was also banned but he successfully compiled the oral narratives of the survivors of 1857 before they died. The book has been translated into English almost a century later. It will fill several research gaps in the scholarship of 1857, which are argely based on English language sources.

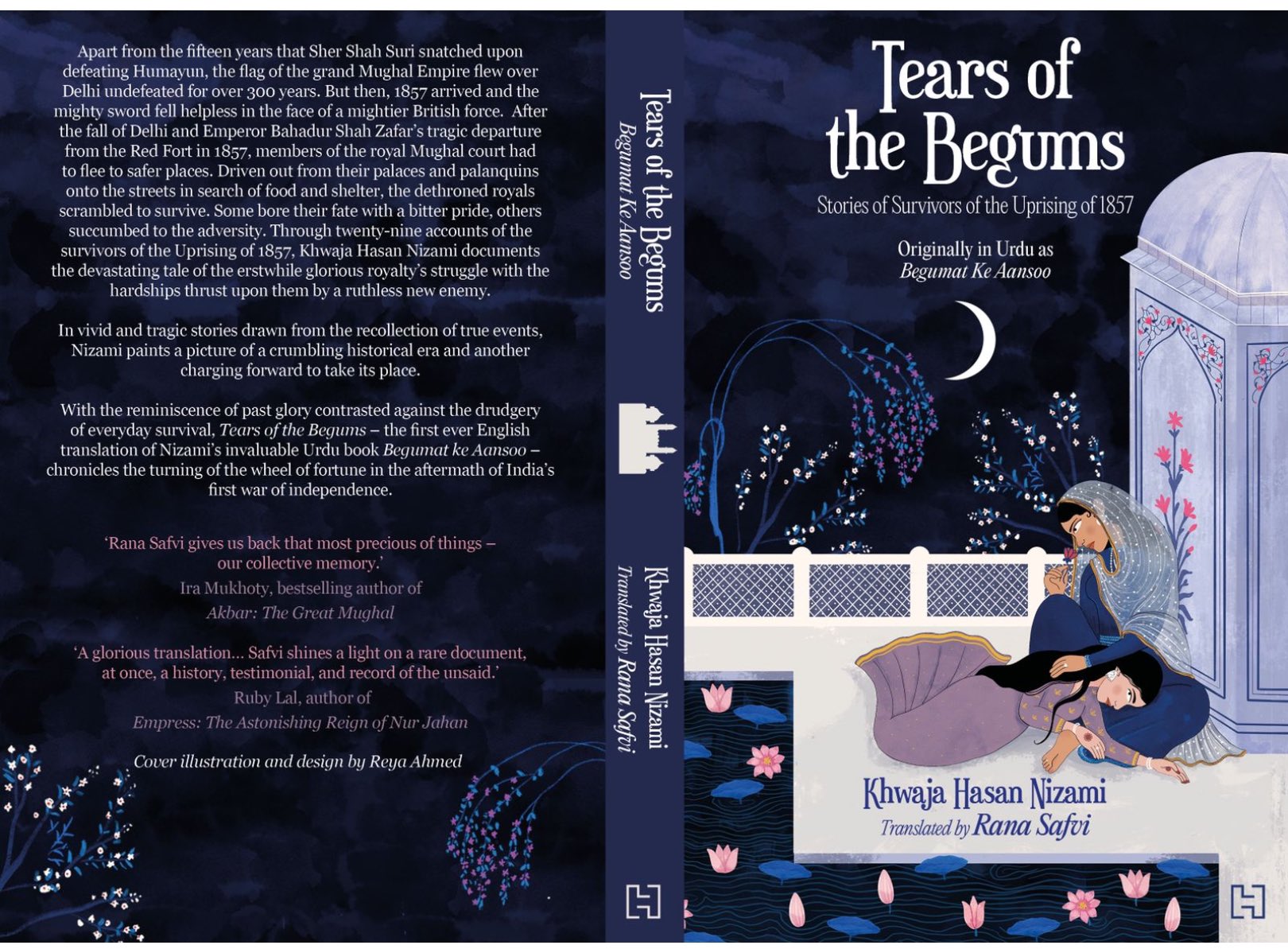

Cover of the Book Tears of the Begums

VD Savarkar, with all the political controversies around him, is credited for writing The War of Indian Independence of 1857 that inspired revolutionary movements in India and placed 1857 as the War of Independence instead of a mutiny. The book luckily got translated, from Marathi to English almost within a few months and gained a wider readership. The book was based upon the official English records and thus in 1909, Savarkar hoped, “a more detailed and yet coherent, history of 1857 may come forward in the nearest future from an Indian pen, so that this humble writing may soon be forgotten!”

In the introduction of the book he wrote, “if some patriotic historian would go to northern India and try to collect the traditions from the very mouths of those who witnessed and perhaps took a leading part in the War, the opportunity of knowing the exact account of this can still be caught, though unfortunately, it will be impossible to do so before very long. When, within a decade or two, the whole generation of those who took part in that war shall have passed away never to return, not only would it be impossible to have the pleasure of seeing the actors themselves, but the history of their actions will have to be left permanently incomplete. Will any patriotic historian undertake to prevent this while it is not yet too late?”

Little did Savarkar know that Nizami was already compiling oral narratives from the survivors. The book remained a talking point among Urdu readers for the last one century. At JNU, when I used to tell people about the book, they would wonder why such an important book had not been translated in English so that they could also incorporate it in their studies. Rana has done a great service to the field of history of 1857 by bringing this book within the reach of the English reading public.

The original book is a compilation of different accounts of the survivors of 1857 narrating the horrors of torture and destruction at the hands of the British after the fall of Delhi. Nizami was a direct descendent of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya and thus the book laces itself with Sufi teachings. The causes and effects of different events have been interpreted through the Sufi worldview. The decline of the Mughal Empire was also seen through the mystical powers of Sufis and Bahadur Shah Zafar was claimed to be a 'dervish’. There are accounts of women fighting the British, princes becoming servants, and other details which will interest any serious scholar of Indian history.

Rana in her translation explains the contexts of events with proper citations, which were not there in the original Urdu. Several anomalies were cleared. In the introduction, Rana writes, “There are contradictions in some places, but it is important to bear in mind that some of the interviewees were old and had experienced immense trauma. Naturally, there are a few mistakes in their recall, but that does not take away from their basis in truth. Wherever I have found any contradictions, I have mentioned them in references. In some stories, the Khwaja has taken the help of a fictionalized narrative as a vehicle to tell the stories he heard, but they remain rooted in fact.”

ALSO READ: Inspiration behind Anandamath believed in Hindu-Muslim unity

I did not discuss the contents of the book as there are no highlights in the book. The book should be read in its entirety. We will be doing a huge disservice if this translation is not available to the students of history and not made available in every library. The translation is as close to the Urdu text as it can be and even if one has read it in its original language, another reading of the translation will captivate the readers.