Faiyaz Ahmad Fyzie

Initially, Dhruv Harsh's film Ilham (2023) appears to be a story of love blossoming between a little boy and his goat. But, in reality, it is a sensitive portrayal of the struggles of the Pasmanda community and their culture. The film brings to the fore a world that was almost invisible to Indian cinema so far.

The protagonist Faizan belongs to the Dhunkar/Dhunia caste (Pasmanda) whose traditional vocation was ginning cotton. The ginning tool is repeatedly depicted in the film, each time reflecting both hope and despair - at times it is a hope for livelihood, and sometimes a symbol of helplessness.

Every scene in the film is steeped in Pasmanda culture and indigenous Indian folk reality. Faizan's mother's request for a bindi, her sewing, and her unravelling of an old sweater to knit a new one all testify to the fact that a woman is not just a housewife but also the backbone of the family's economy. The life of a Pasmanda woman is a blend of hard work, patience, and compassion, who, despite living on the margins of society, remains the pillar of the entire family.

The courtyard of Faizan's house displays telltale signs of a traditional Pasmana home: the wooden bed, a bottle used to collect water from the hand pump, his grandfather wearing lungi-ganji, keeping the mattress folded on one edge of the bed during the day. All these are stereotypical images of a Muslim household that Bollywood is not too fond of showing. These images are not artificial but are organic. These are not about the false pride of the "Nawabiyat" of Lucknow, nor the sugary sweetness of the Urdu language that Bollywood makes us believe all Muslims speak. Life in a Pasmanda household has rough edges.

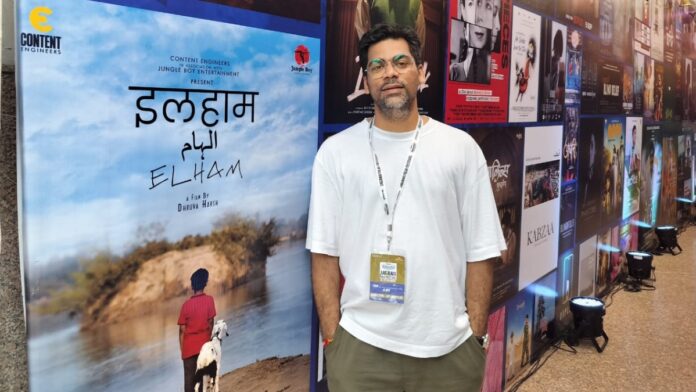

Filmmaker Dhruv Harsh's film with posted of his film Ilham

Indian cinema has so far portrayed Muslim families as either wealthy nawabs or religious fanatics, but Ilham takes us into indigenous Pasmanda homes, perhaps for the first time.

The dialogue of the film is vernacular. When Faizan's grandfather is worried about his son Rafiq as he has has not returned home, he says, "Gaudhuli beet gayi: Rafiq aaya nahim aab tak (Dusk has passed, but Rafiue has not returned)," it's the common language of a villager in many parts of north India. Similar dialogues bring to the fore the limited employment opportunities for the Pasmanda Muslims.

Words like Godhuli are of Hindu tradition, but these are a natural fit in the Pasmanda dialect. This authentically reveals the roots of Pasmanda life. In other words, the Pasmanda dialect is the bridge between Hindu tradition and Muslim life. The two merge and enrich the culture of India. This culture does not originate from any Delhi court or Aligarh library, but from the dust and sunshine of the village.

This is where the film reveals that Pasmanda identity is not merely religious, but based on the power of labour. Dhruv Harsh has shown with remarkable sensitivity how even religious rituals become a burden for poor Pasmanda families.

Filmmaker Dhruv Harsh at a film festival

Filmmaker Dhruv Harsh at a film festival

Taking a goat past the temple is a symbol of the simplicity of the Pasmanda community living in a Hindu-dominated village. This scene proves that the life of the Pasmanda community is deeply connected to Indian culture and away from communalism.

Therefore, Ilham not only creates the ideal of communal harmony but also vividly portrays the innate Indianness of Pasmanda life. The most courageous aspect of the film is its ideological message. When a character says, "Don't get into this newspaper-related mess",—this dialogue actually raises a question mark on the media's reporting of communalism. In this way, the film, through its small dialogues, also cautions against communalism.

Ilham shows how poverty, caste-based occupations, religious pressures, and social discrimination combine to create the world of the Pasmanda. This is why the film doesn't become an 'ideal story' of communal harmony. It simply attempts to bring to light the lives of the Pasmanda community, who are deeply rooted in Indian soil.

Ilham is extremely mature in terms of cinematic craft. Ankur Rai's camera captures the streets and fields of Awadh with such intimacy that the viewer feels a part of that landscape. Music composer Vicky Prasad has used folk tunes and silence in such a way that the soul of the story is automatically revealed. Every movement of the camera, every frame makes the viewer a living part of reality.

Acting is the film's most solid foundation. The child actors playing Faizan and Fatima didn't just act; they brought the characters to life. Guneet Kaur's performance as Faizan's mother is remarkable, bringing out both the patience and compassion of a Pasmanda woman. Her performance brings to life the silence and tolerance that is written on every Pasmanda woman's face.

Filmmaker Dhruv Harsh with fans

Filmmaker Dhruv Harsh with fans

These international platforms have given Elham a distinct identity at the national and international level, not just as a film, but by creating a new identity for Indian children's cinema. The reactions of film critics have also been very positive.

The magic of Dhruv Harsh's film is that it blurs the difference between reality and cinema. The viewers feel they are part of the story and not mere spectators.

Ilham breaks the monotonous image of the Muslims, who are either 'Nawabi' or 'fanatic religious' people with kohl-rimmed eyes and skull caps, out to destroy the world. Ilham has given the world the realism about native Indian Muslims.

This world, seen through Faizan's eyes, is the world of Pasmanda childhood. He has innocent desires and dreams that have to be sacrificed at the altar of societal discrimination. Dhruv Harsh has tried to give a place to Pasmanda life in the mainstream Indian cinema. Till now, the mainstream cinema had limited the Muslim identity to Nawabi style, Urdu rhetoric or poetry. Elham has tried to bring it to the indigenous Pasmanda Muslims.

This film not only stands as a milestone in Indian children's cinema, but also gives a powerful cinematic portrayal of Pasmanda reality. There is no doubt that Ilham has carved a special place for herself in the history of Indian cinema by presenting the true picture of Pasmanda life.

ALSO READ: Raunaq Anwar's journey from teaching texts to ramp walks

Ilham has, perhaps for the first time, made the Pasmanda community not the 'subject' but the 'hero' on screen. Ilham has proved that without understanding the Pasmanda life, any picture of Indian society and Indian cinema is incomplete.

(Dr. Fayaz Ahmad Faizi, writer, translator, columnist, media panelist, Pasmanda-social worker and Ayush doctor)