Amir Suhail Wani/Srinagar

Two decades after his passing, Kashmiri painter-poet G. R. Santosh continues to be celebrated as a visionary who incorporated Kashmir's philosophies of Shaivism and tantra into his works, and, was therefore one of the most renowed painters of his times.

Experts says his paintings invited viewers into luminous geometries of being, while his poetry gave voice to the yearning of the soul. Together, they reveal a life lived in pursuit of the eternal.

In Santosh, the worlds of art, literature, and philosophy converged, creating a legacy that transcends time and geography. It was his spiritual quest that, in the prime of his youth, Santosh took to the study of Tantric texts and their secretive rituals.

Born as Ghulam Rasool Dar in 1929 in a village, Dab, on the outskirts of Srinagar city, he later took to Santosh as his name. Later, the family moved to Chinkral Mohalla, a downtown locality where he was raised in a modest Kashmiri Muslim family. The early death of his father disrupted his education and forced him to assume responsibilities prematurely.

A painting of G R Santosh

A painting of G R Santosh

These difficulties, however, never dimmed his innate artistic temperament. Instead, they cultivated in him an unusual resilience and sharpened his sensibilities, enabling him to perceive the beauty of Kashmir’s natural and cultural landscape with rare intensity.

As a boy, Santosh had to take up small jobs to sustain his family: painting signboards, weaving silk, crafting papier-mâché items, and assisting masons. These early experiences exposed him to Kashmiri craft traditions, instilling in him a respect for precision, texture, and patience.

Alongside, he nurtured a growing love for art. Under the guidance of local painter Dina Nath Raina, he learned watercolour landscapes.

In 1945, he completed his matriculation with painting as a subject, a rare achievement for someone of his modest background. His early drawings, often of Srinagar’s landscapes and bustling bazaars, reflect both a documentary instinct and a budding poetic vision.

Santosh’s life took a decisive turn in 1954, when he received a scholarship from the Jammu & Kashmir government to study at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. At Baroda, he studied under the legendary N. S. Bendre, who introduced him to modernist principles, colour theory, and formal experimentation. Santosh encountered cubism, post-impressionism, and the currents of Indian modernism that were reshaping the national art scene after independence.

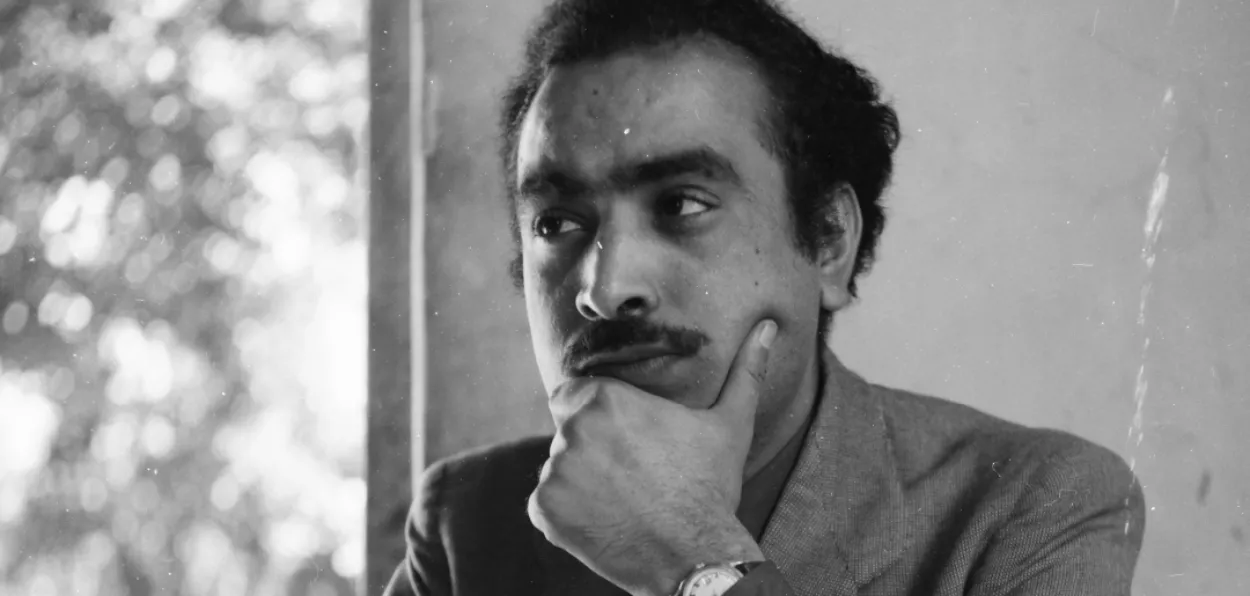

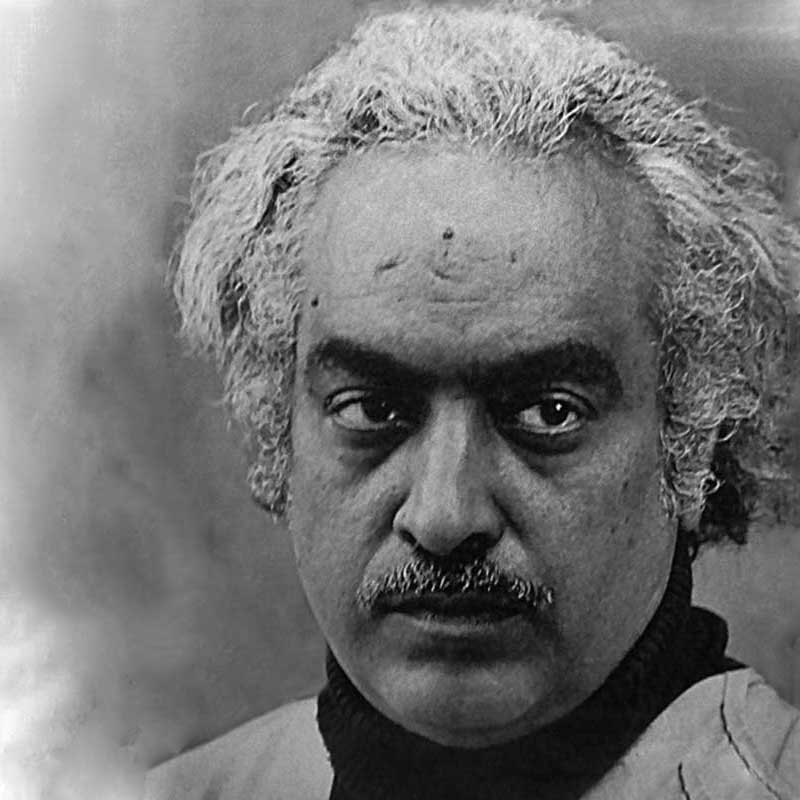

G R Santosh

G R Santosh

Yet, even as he absorbed these idioms, his imagination remained tethered to the metaphysical underpinnings of his Kashmiri heritage. His student works reveal an artist negotiating between the outer forms of modernism and the inner pull of mysticism.

The most profound shift in Santosh’s journey came in 1964, when he undertook a pilgrimage to the Amarnath Cave. The vision of the naturally formed ice lingam inside the cave acted as a spiritual initiation, awakening in him a deep yearning to explore the mysteries of consciousness and divinity. Returning from this pilgrimage, he immersed himself in Kashmiri Shaivism and Tantra, guided by the teachings of Swami Lakshman Joo, the foremost Shaiva scholar of his time. Santosh studied Tantric texts and absorbed their cosmological symbolism—concepts of prakash (illumination) and vimarsha (self-reflection), the dance of Shiva and Shakti, and the meditative diagrams of yantras and mandalas.

This marked the beginning of his Neo-Tantric period. His canvases became radiant fields of geometry and colour: circles, triangles, squares, and lotus motifs, composed with rigorous symmetry and vibrant palettes of red, blue, white, and gold. These forms, far from mere abstractions, functioned as metaphysical diagrams—maps of the cosmos and the inner self. His art embodied the tantric principle that form is energy, and energy is consciousness. To gaze upon his canvases was to enter a meditative space, vibrating with transcendence.

Santosh’s mastery of this idiom earned him wide acclaim. He received the National Award from the Lalit Kala Akademi in 1957, 1964, and 1973, and in 1977, he was honoured with the Padma Shri, one of India’s highest civilian awards. His recognition was not confined to the visual arts alone. Writing in Kashmiri and Urdu, Santosh proved himself an equally accomplished poet. His collection Be Soakh Rooh (The Burnt Soul) won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1979. Few Indian creative figures have been celebrated at the highest level in both literature and painting, marking Santosh as a truly unique personality.

His art achieved global visibility as well. He represented India at the São Paulo Biennial in 1969 and the Paris Biennale, and he participated in successive editions of the Triennale-India. In 1985, a major solo exhibition at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) introduced his work to American audiences. These international platforms placed him in dialogue with global abstraction, but Santosh’s art remained distinct for its rootedness in Kashmiri metaphysics. Unlike artists who used tantric symbols for surface appeal, Santosh’s work was steeped in lived philosophy and genuine spiritual inquiry

Santosh’s poetry complements his visual art, offering another window into his mystic vision. His verses grapple with anguish, longing, ecstasy, and the search for divine unity. They echo the same currents that animate his paintings: the oscillation between the finite and the infinite, the visible and the invisible. For Santosh, poetry was meditation in sound and rhythm, while painting was meditation in colour and form. Together, they formed a seamless creative continuum. His poetic style—simultaneously lyrical and metaphysical—places him in the lineage of Kashmiri mystic poets such as Lalla Ded and Habba Khatoon, though with a distinctly modern sensibility.

G. R. Santosh’s death on 10 March 1997 in New Delhi closed a luminous chapter in Indian art, but his legacy endures powerfully. He is remembered as one of the foremost figures of the Neo-Tantra movement, a pioneer who harmonized modern abstraction with Kashmir’s ancient Shaiva philosophy. His works remain touchstones of Indian modernism, celebrated for their spiritual intensity, luminous precision, and symbolic depth.

Critics and scholars continue to engage with his oeuvre, noting both its brilliance and its challenges. For some, the heavily symbolic language of his art makes it difficult for general audiences to fully grasp. For others, this very depth elevates his paintings beyond mere aesthetics, turning them into vehicles of meditation and self-discovery. His poetry, less widely known than his paintings, nonetheless stands as a vital part of his legacy, resonating with themes of transcendence and existential struggle.

READ MORE: Mand exponent Batool Begum is a living legend of Indian culture

Santosh’s dual recognition—as a painter and a poet—remains rare in modern Indian culture. He embodied the archetype of the artist-mystic, bridging the spiritual traditions of Kashmir with the universal language of modernism. His art continues to inspire younger generations of artists who seek to engage with India’s philosophical traditions in contemporary idioms.