Saquib Salim

Saquib Salim

“This last week, the Bombay leaders have again given proof of their organising power. They brought together a National Congress composed of delegates from every political society of any importance throughout the country. Seventy-one members met together; 29 great districts sent spokesmen. The whole of India was represented from Madras to Lahore, from Bombay to Calcutta. For the first time, perhaps, since the world began, India as a nation met together. Its congeries of races, its diversity of castes, all seemed to find common ground in their political aspirations.”

This is an excerpt from the report published by The Time's (Weekly Edition) on 5 February 1886.

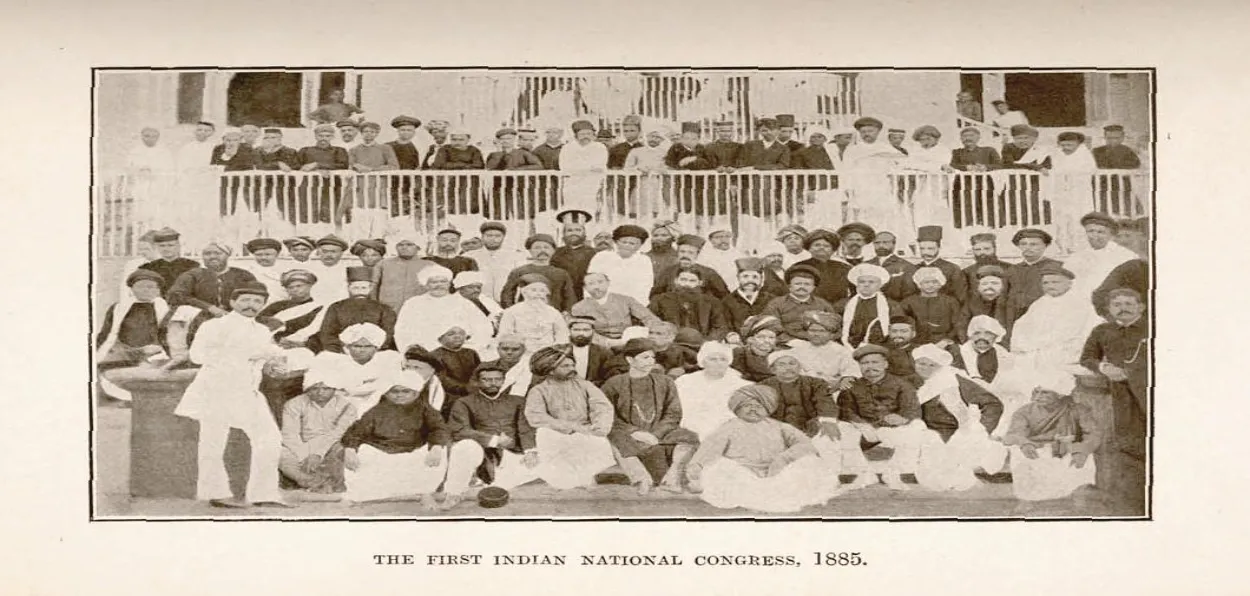

On 28 December 1885, 72 representatives and 30 observers from across India attended the first session of the Indian National Congress. This marked a new chapter in the Indian freedom struggle, in which local efforts were brought under an umbrella of law and constitutionality.

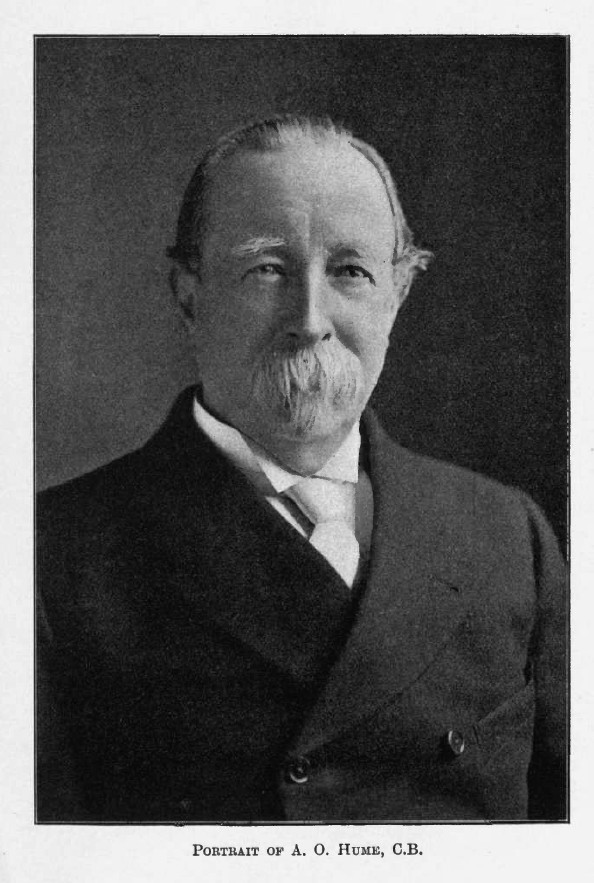

A retired British official and ornithologist, with the help of several Indian political thinkers, issued a circular in March 1885 inviting Indians to attend the first session of the Indian National Congress. The circular said, "A conference of the Indian National Union will be held at Poona from the 25th to the 31st December 1885.

"The conference will be composed of delegates, leading politicians well acquainted with the English language, from all parts of the Bengal, Bombay and Madras Presidencies."The direct objects of the conference will be: (1) to enable all the most earnest labourers in the cause of national progress to become personally known to each other; (2) to discuss and decide upon the political operations to be undertaken during the ensuing year.

“Indirectly, this conference will form the germ of a native parliament and, if properly conducted, will constitute in a few years an unanswerable reply to the assertion that India is still wholly unfit for any form of representative institutions. The first conference will decide whether the next shall be again held at Poona or whether, following the precedent of the British Association, the conferences shall be held year by year at different important centres.”

The initiative followed earlier formations of the Indian Association, Indian Union, the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, the Bombay Presidency Association, etc. The invitation for its first meeting said, “The Peshwah's Garden near the Parbat Hill (Pune) will be utilised both as a place of meeting (it contains a fine Hall, like the garden, the property of the Sabah) and as a residence for the delegates, each of whom will be provided with suitable quarters. Much importance is attached to this, since, when all thus reside together for a week, far greater opportunities for friendly intercourse will be afforded than if the delegates were (as at the time of the late Bombay demonstrations) scattered about in dozens of private lodging houses all over the town.”

A few days earlier, the Cholera epidemic broke out in Pune and forced a last-minute change in the venue of the event. Bombay Presidency Association was entrusted to hold the session at Gokuldas Tejpal Sanskrit College at Gowalia Tank in Mumbai on 28 December 1885. The official report stated, “Very close on one hundred gentlemen attended, but a considerable; number of these being Government servants, ……, did not (with one exception) take any direct part in the discussions, but attended only as Amici curie, to listen and advise, so that the actual number of Representatives was, only so far as the records go, (though it is feared some few names have been omitted from the Register) 72,...”

A few days earlier, the Cholera epidemic broke out in Pune and forced a last-minute change in the venue of the event. Bombay Presidency Association was entrusted to hold the session at Gokuldas Tejpal Sanskrit College at Gowalia Tank in Mumbai on 28 December 1885. The official report stated, “Very close on one hundred gentlemen attended, but a considerable; number of these being Government servants, ……, did not (with one exception) take any direct part in the discussions, but attended only as Amici curie, to listen and advise, so that the actual number of Representatives was, only so far as the records go, (though it is feared some few names have been omitted from the Register) 72,...”

The Bombay Gazette reported, “.... the spectacle which presented itself of men representing the various races and communities, castes and sub-divisions of caste religions and sub-divisions of religions met together in one place to form themselves, if possible, into one possible whole, was most unique and interesting.”

On December 28, the first session started at 12 noon, and it unanimously chose W. C. Bonerjee as the President of the Congress.

Although it was a small beginning and all the members pledged their loyalty to the British crown, the British press and the empire sensed the threat. Time's tried to downplay the Congress by claiming, “Only one great race was conspicuous by its absence; the Mahomedans of India were not there. They remained steadfast in their habitual separation….. But, in spite of the absence of the followers of the Prophet, this was a great representative meeting last week.”

The editorial on the one hand prophesied the future course of the Congress and on the other argued that it would fail in its objective.Time's Editorial said, “The first question which this series of resolutions will suggest is whether India is ripe for the transformation which they involve. If this can be answered in the affirmative, the days of English rule are numbered. If India can govern itself, our stay in the country is no longer called for….. Those who know India best will be the first to recognise the absurd impracticability of such a change. But it is to nothing less than this that the resolutions of the Congress point. If they were carried out, the result would soon be that very little would remain to England except the liability which we should have. assumed for the entire Indian debt….. Our correspondent tells us that the delegates fairly represent the education and intellectual power of India. That they can talk, and that they can write, we are in no doubt at all. The whole business of their lives has been training for such work as this.

"But that they can govern wisely, or that they can enforce submission to their rule, wise or unwise, we are not equally sure. That the entire Mahomedan population of India has steadily refused to have anything to do · with them is a sufficiently ominous fact. Even if the proposed changes were to stop short of the goal to which they obviously tend, they would certainly serve to weaken the vigour of the Executive and to make the good government of the country a more difficult business than it has ever been. The Viceroy's Council already includes some nominated native members. To throw it open to elected members, and to give minorities a statutable right to be heard before a Parliamentary Committee, would be an introduction of Home Rule for India in about as troublesome a form as could be devised.”

The Time's emphatically declared, “But it was by force that India was won, and it is by force that India must be governed, in whatever hands the government of the country may be vested. If we were to withdraw, it would be in favour not of the most fluent tongue or of the most ready pen, but the strongest arm, and the sharpest sword.”

The British media understood the potential threat from the Indian National Congress. Since then, the media continued its propaganda that Muslims are not with Hindus.

On 9 March 1886, K. T. Telang refuted the charges made by Time’s. In a letter to the editor, he wrote, “Although it must be admitted that the Mahomedan community was not adequately represented at our meeting, your remark is not altogether an accurate one. Two leading Mahomedan gentlemen did attend the Congress, viz., Mr R.M. Sayani and Mr A.M. Dharamsi… Further, the Hon. Mr Badroodin Tyabji, a member of the Legislative Council at Bombay, and Mr Cumroodin Tyabji would have attended the Congress, had they not been absent from Bombay at the time the Congress was sitting. Mr Badroodin is Chairman of the Managing Committee and Mr Cumroodin, one of the Vice-presidents of the Bombay Presidency Association, which, in concert with the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, convened the Congress.”

ALSO READ: 2025: Peace firmed its roots in Kashmir, despite Pahalgam attack

The Congress soon became an organisation of nationalists served by the likes of Lokmanya Tilak, G. K. Gokhale, Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai and others. Mahatma Gandhi turned it into a mass movement, which had Jawaharlal Nehru, Subhas Chandra Bose, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Sardar Vallabbhai Patel and other stalwarts in its ranks. India fought and won the freedom struggle under the aegis of the Indian National Congress, formed on this day.