New York

A spacecraft the size of a cereal box has collected precise measurements of the atmospheres of large and puffy exoplanets called "hot Jupiters".

As their name suggests, hot Jupiters are gas giants like our own Jupiter. These planets, however, hug much closer to their home stars, completing an orbit roughly once every several Earth days.

In the process, stellar radiation cooks hot Jupiters to thousands of degrees Fahrenheit, and their atmospheres swell to enormous sizes, a bit like bread rising in an oven.

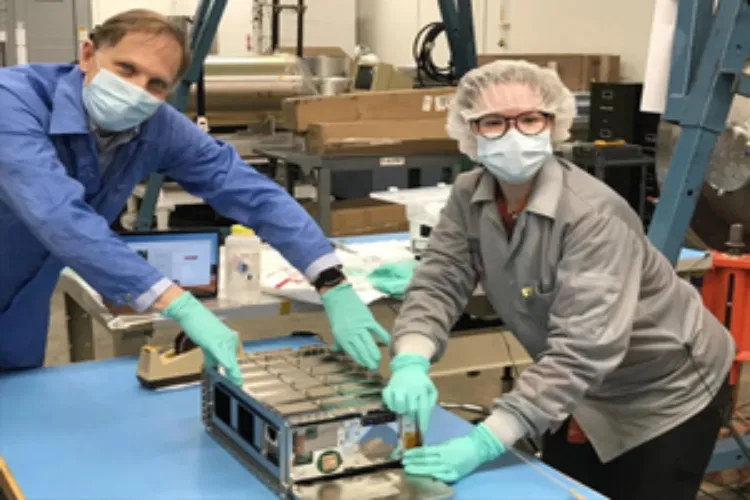

The spacecraft, Colorado Ultraviolet Transit Experiment (CUTE), measuring just 14 inches in length, has observed seven hot Jupiters so far.

Some of them seem to be losing their atmospheres, but others aren’t.

Researchers have long suspected that this constant pummeling from stellar radiation could strip away the atmospheres from around some exoplanets over millions-to-billions of years.

Data from CUTE suggest that the process might not be so simple.

"The planets seem to be coming in all of the flavours," said Kevin France, principal investigator and Associate Professor in the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) and Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences at the University of Colorado-Boulder.

He added that CUTE is helping scientists to build out their field guide to the many kinds of planets that exist in the Milky Way Galaxy -- including those that look nothing like Earth’s close neighbours.

"We want to understand how our solar system fits into the family of solar systems in the universe," France said.

"That means understanding the big planets, the small planets, the ones that have life and the ones that definitely don’t -- and all of the important physical processes that are operating on these planets."

CUTE observes distant planets as they pass in front of their home stars, causing ultraviolet light from those stars to dim in the process. In some cases, the spacecraft is so precise that it can detect when starlight dims by just 1 per cent.

France will present the results at the ongoing 2023 meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. Launched in September 2021, CUTE is currently orbiting about 525 km above Earth’s surface, and is expected to reenter the atmosphere by 2027.