Saquib Salim

Saquib Salim

Prof. Abdul Shaban of ther Tata Institute of Social sciences (TISS) writes, “Given the fear of riots, economic inability and discrimination in the housing market due to their religious identity, Muslims largely remain locked inside their ghettoes in older parts of the cities. These ghettoes remain characterised by the lack of development and fear of others.”

Justice Rajindar Sachar-led committee, in its report on the Social, Economic and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India, also noted, “However, while living in ghettos seems to be giving them a sense of security because of their numerical strength, it has not been to the advantage of the Community. It was suggested that Muslims living together in concentrated pockets (both because of historical reasons and a deepening sense of insecurity) have made them easy targets for neglect by municipal and government authorities. Water, sanitation, electricity, schools, public health facilities, banking facilities, anganwadis, ration shops, roads, and transport facilities are all in short supply in these areas.

"In the context of increasing ghettoisation, the absence of these services impacts Muslim women the most because they are reluctant to venture beyond the confines of ‘safe’ neighbourhoods to access these facilities from elsewhere. Increasing ghettoisation of the Community implies a shrinking space for it in the public sphere; an unhealthy trend that is gaining ground.”

Scholars, analysts and intellectuals are almost unanimous on the account that ghettoisation of Muslims has had a detrimental effect on the development of this largest religious minority in India. The process started long before independence in the early 20th century, when Hindu-Muslim riots started threatening the people, especially in urban spaces. Around this time, segregation started, and it became more pronounced after the partition. Muslims wanted to live among ‘their own’ and Hindus did not want ‘others’ in their areas.

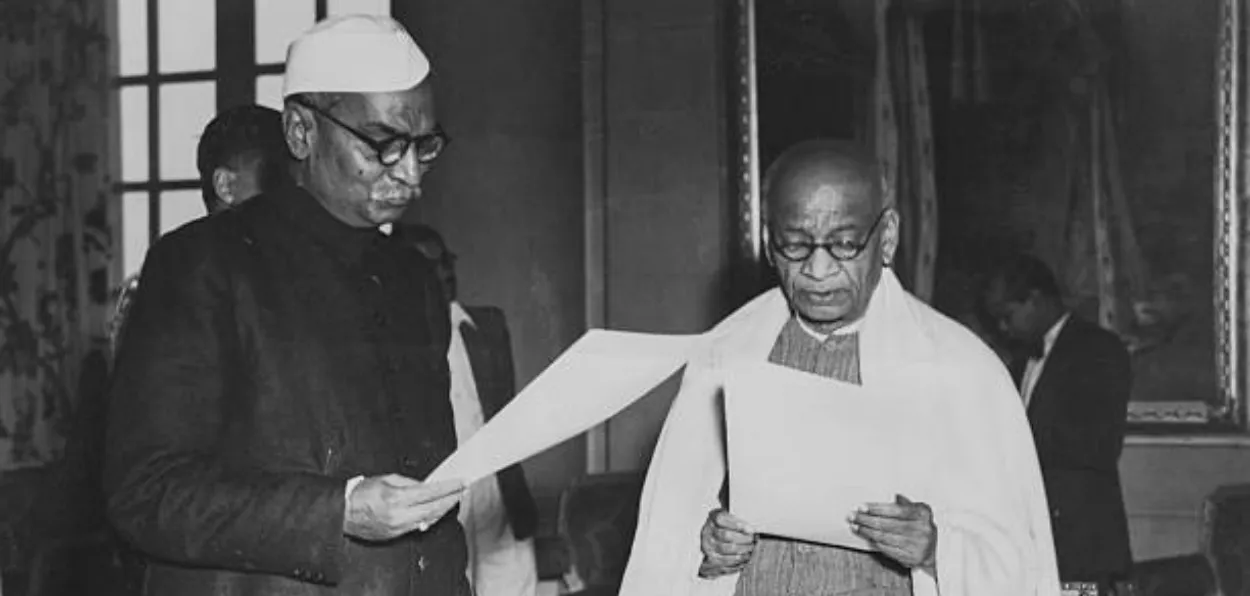

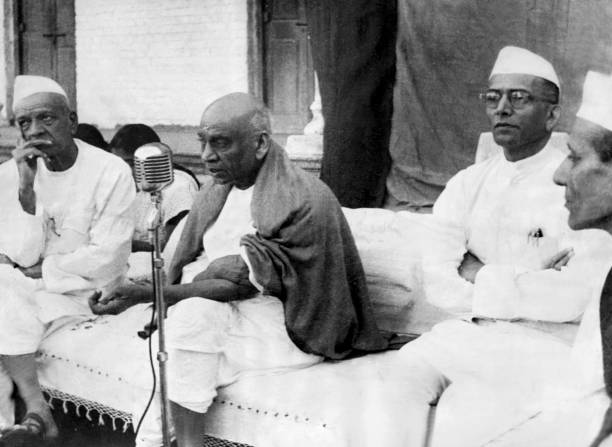

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel with Morarji Desai and Choudhary Charan Singh

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel with Morarji Desai and Choudhary Charan Singh

Most of the Indian politicians, including Jawaharlal Nehru, considered it a legitimate wish. They believed that Muslims have every right to have their ‘safe spaces’. But Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel had a different view. Right from the beginning, he was against the idea of ‘exclusive space for a community’. He foresaw that such a policy would lead to the ghettoisation of a community and would stop its integration into the mainstream of national life.

In the aftermath of the partition, when Hindu and Muslim populations were being exchanged between India and Pakistan, a huge influx of refugees poured in Delhi as well. On 21 November 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru wrote to Sardar Patel that non-Muslims should not be allotted the houses in Muslim dominated localities on account of their owners' migrating to Pakistan. He believed that this would create problems and Muslims would feel unsafe living with non-Muslims.

Sardar Patel replied that he was against the constitution of Muslim pockets and Hindu pockets in the city. This, in his view, would increase the enmity between the two groups and minimise their interactions. He agreed on the need to check the character of occupants but not their religions, before allotting them the vacant houses.

On 9 December 1947, Sardar Patel replied to K. C. Niyogi, on his suggestion that to deal with refugees and riot victims, only their coreligionist government employees and police should be deployed, that such an approach would create further rift in the society. He believed that such an approach would further divide an already divided society. At least the government could not reinforce the communal cleavage in its policies.

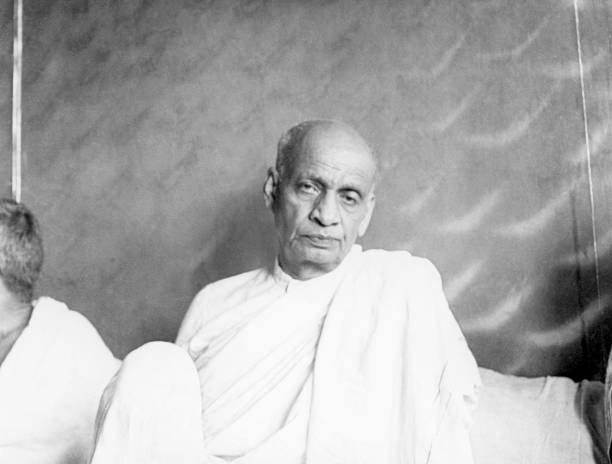

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

Sardar Vallabhbhai PatelThe often levelled allegation that Sardar Patel’s policies were anti-Muslim doesn’t stand ground if we see his commitment to the belief in Hindus and Muslims living in a mixed society in a secular India. On 5 September 1947, Dr Rajendra Prasad wrote to Sardar Patel that he should reduce the number of Muslim police personnel in Delhi because the Hindu population did not feel secure in their presence. He also asked for providing arms to Hindus for self defence and cancelling licenses of Muslim arms dealers in Delhi.

Rajendra Prasad was one of the senior leaders, and it was difficult to say no to him. Sardar Patel told him that these police officers were permanent employees and until they chose to go to Pakistan, they could not be removed. About arms, he said that he could not formulate a more liberal policy for arms distribution because they were not “sure if these arms would not be used against the Muslims.”

Sardar Patel did not believe that Hindus and Muslims should live in separate pockets or that coreligionists should serve the people. In his view, India could prosper only if people lived together, intermingled, and served each other. This was true to the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, who asked Anis Kidwai to serve Hindu refugees after her husband was killed by a Hindu mob because he believed that only through intercommunal interactions would we defeat communalism.

Ghettoisation of Muslims would become a problem for Muslims themselves, as foreseen by Sardar Patel in 1947. His ideas at the time were dubbed by many as anti-Muslim.

ALSO READ: Is mixed housing a solution to growing Hindu-Muslim chasm?

In 1949 Sardar Patel said in Hyderabad, “The Muslims are not foreigners. They are from among ourselves. Gandhiji always proclaimed that if we want true Swarajya, we should do away with untouchability; We should unite Hindus and Muslims... ..In our secular state, we have tried to ensure that Muslims enjoy all their rights as equal citizens.”