Raziuddin Aquil

Raziuddin Aquil

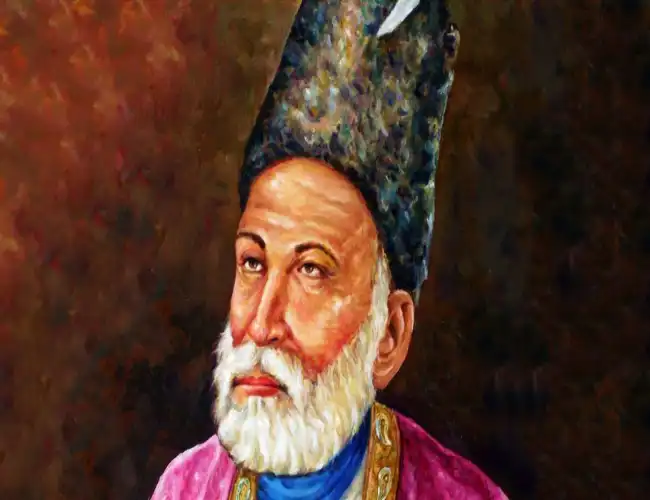

This piece highlights the terrible predicament of the last Mughal poet, Mirza Ghalib, during the horrendous violence in the wake of the revolt of 1857. Ghalib has expressed his anguish and sorrow in his autobiographical narrative, deceptively titled, Dastanbu, fragrance of my hands. Historians have tried to ignore the poet, but through scholars of Urdu literature and on the strength of his own powerful poetry of love, ghazal, Ghalib‘s legacy of melancholy has an everlasting audience.

The last Mughal poet of Delhi, Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib (1797–1869), has presented a miserable account of his own plight during the revolt of 1857 in his heart-wrenching autobiographical diary-like text, deceptively titled Dastanbu, meaning pleasant fragrance of my hands. Mirza Ghalib had to face immense difficulties during those 15 months of trials and tribulations of 11 May, 1857 to 30 July, 1858. This was especially so because his family pension from the British government was discontinued immediately after the outbreak of the revolt. The struggle for renewal of this pension remained an enduring story of Ghalib’s life thereafter.

The revolt of the Indian soldiers and the attack on the British and the heinous actions by the latter in revenge badly affected the sixty-something Mirza Ghalib. The devastation at home and outside and the dreaded havoc caused all around are evident on every page of Dastanbu. The British revenge against the rebellion fell especially on Muslims. Ghalib writes that although his house was not directly looted by British soldiers, he had lost all his valuables and was also picked up for interrogation. Meanwhile, the pension regularly received from the British was stopped, as he was known for his association with the Mughal court.

The Book Corner

Ghalib has himself provided a valuable historical perspective by throwing light on his life and work in Dastanbu. He says that the year 1857 coincided with sixty-second year of his life of which nearly fifty years were spent on a poetic journey, of sher-o-shayri. He was just five when his father Abdullah Beg Bahadur had passed away. His uncle Nasrullah Beg Khan Bahadur brought him up like a son, but he also died when Ghalib was only nine-year-old.

Commanding 400 soldiers, Ghalib’s uncle was in the service of British general Lord Lake, who had ensured two parganas near Agra as his jagir. After his death, the British government withdrew both the parganas. Instead, a monthly stipend was fixed for Ghalib and his younger brother, Mirza Yusuf, who incidentally died during the revolt after a prolonged mental disorder from which he suffered. The stipend was continuously received from the treasury of Delhi Collectorate till April 1857. Unfortunately, the door of that treasury was closed with the rebellion which broke out in May that year. This is despite the fact that Ghalib was sharply critical of the revolt and has written about it in this text.

The Book

The British were able to quickly recover in Delhi, but as Ghalib writes the situation was tense and rebel gangs were active for months in many towns and localities. He condemned them harshly, writing that many rebels were resorting to violence. According to him, they were unnecessarily fighting a lost battle. He feared that the stronger the struggle against the British, the more oppressive the latter would become in their retaliation. He, therefore, cursed the rebels, called the British just rulers and continuously reiterated his loyalty towards them. Meanwhile, he also continued to cultivate his personal relations and friendship with British officials, but the administration was not moved.

What was Ghalib’s crime or fault? Did he commit any mistake to displease his British patrons? The answer is the British knew that Ghalib was not only a famous poet, but he was also a historian associated with the Mughal court. New political regimes seek to crush the historians associated with previous governments. They want to write history on the body of those they subjugate. Ghalib tried his best to get the British to accept him. The poet opposed the revolt of 1857 for this purpose. He also pleaded that the readers of his book should know that for all the magic of his pen when put to paper, he had depended on his livelihood on the British since his childhood, literally picking up grains from their dining table. However, none of these rhetoric helped. The finest Urdu poet of the 18th century, Mir Taqi Mir, would have anticipated the predicament:

Ulti ho gayin sab tadbiren kuchh na dawa ne kaam kiya

Dekha is bimariye dil ne akhir kaam tamam kiya

Historians can learn some lessons from Ghalib’s tragedy, in terms of maintaining critical distance from political regimes, but then is it possible to steer clear of political power and remain neutral either? Can one also remain neutral in the wake of political violence all around? What may have put off the British with regard to Ghalib was that he was attempting to ride two horses simultaneously.

He has defended his position thus: 7-8 years back the Emperor called him to the court and asked him to write a new history of Timurid dynasty, for which an annual stipend of Rs 600 was fixed. He had accepted this job and got busy with work. After a while, the Emperor’s mentor or teacher in Urdu poetry (ustad), Zauq Dehlawi, passed away, and the responsibility of correcting and polishing the Emperor’s poetry was also assigned to Ghalib.

Thus, Ghalib was not only writing an official history of the Mughals, but he was also honoured with the status of Bahadur Shah Zafar’s master in Urdu shayari. During the revolt and after it was crushed, the precarious position of the Mughal emperor’s close associates can be easily gauged. Many influential people were hanged, a large number of ordinary ones were also robbed and hacked even inside their homes. The Emperor himself was banished to Rangoon. Undoubtedly, the British showed their kindness to Ghalib by not harming him physically, though his pension was stopped, which could not be released again.

ALSO READ: Kadka at Ajmer Dargah represents India's syncretic culture

Referring to his job in the fort, Ghalib has pleaded that he had grown old and weak, and was accustomed to sit and rest away from the crowd, in a corner of his house. Also, because of increasing loss of hearing, deafness, he was unable to properly follow what people spoke at court and other public gatherings. He would, thus, force himself to visit the fort once or twice a week. If the emperor appeared in diwan-i-khaas, he would remain in his presence, otherwise he would leave after sitting there for some time. During this period, whatever work was completed, he would carry with him or send through someone. This was the sum total of his work and connection with the court. For the British, this may have sounded like the usual story of Indian deception they were accustomed to hear from the people they had colonised.

Seen from Ghalib’s point of view, it is a matter of regret that all his efforts to gain the trust of the British had failed. On the other hand, because of his opposition to the revolt of 1857, Indian nationalist historiography, of which there are several strands, has also deemed it necessary to steer clear of Ghalib’s life and career. Thankfully, scholars studying Urdu literature and its history have preserved Ghalib’s name and identity, besides his gaining immense popularity in posterity, across regions beyond Urdu speaking areas.

On his own, grappling with all the problems, Ghalib stood firm on his iconoclastic assertions:

Hoga koy iaisa bhi ke ‘ghalib’ ko najaane

Shayar tow woh achcha par badnam bahot hai

And:

Puchhte hain woh ke ghalib kaun hai

Koyi batlao ke ham batlayen kya

(Raziuddin Aquil is Professor of History, University of Delhi. Excerpted from his recently published book, History in the Public Domain, Manohar Books).