Saeed Naqvi

Saeed Naqvi

An implausible story making the rounds on social media has its origins in an extraordinary initiative launched by the External Affairs Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee and his Foreign Secretary Jagat Mehta in 1979 when New Delhi’s relations with Iran suddenly evaporated with the fall of the Shah and the Ayatollah’s ascent to power in Tehran.

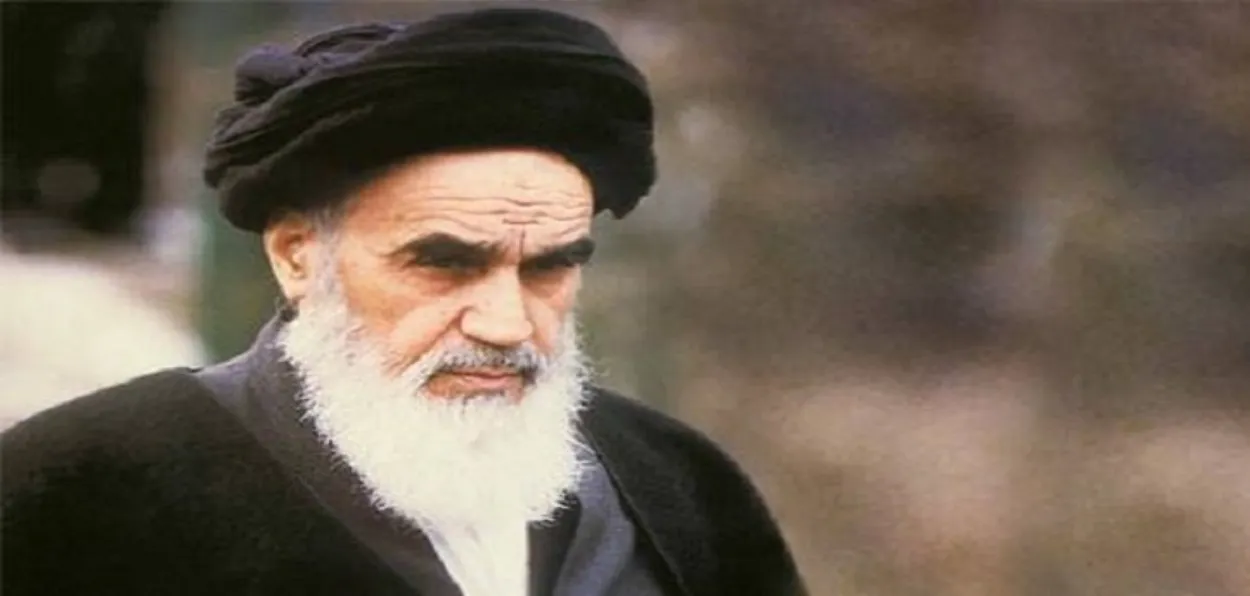

Ayatollah Ruhullah Khomeini, the first Supreme Leader of the Islamic Revolution, spent years in exile in Najaf (Iraq) and, towards the end, in Neuchâtel le Chateau outside Paris.

What is generally not known is that Lucknow and Qasbahs around have been centers of Shia learning since the mid-18th century. This was when Nawab Saadat Ali Khan, the first Nawab of Awadh, established the Shia kingdom, first in Faizabad, and later moved to Lucknow. Saadat Ali Khan traced his origins from Nishapur, in Khorassan, South of the Shrine in Mashhad of Imam Reza, the eighth Imam of the Shias.

The last Nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah, reveled in cultural commerce between communities. He played a rather portly Radha while the Kathak Guru Pandit Binda Deen, the great-great-grandfather of the late Birju Maharaj, danced as Krishna.

Under the Awadh Nawabs composite Ganga-Jamuni culture flourished. Along with song, dance, and theatre, centers of Shia learning also mushroomed in Lucknow and its vicinity, including Kintoor in the Barabanki district.

When the Ayatollahs came to power in Iran, a pertinent question arose. Since Lucknow at one stage was the “markaz” or centre of Shia theology, were there any linkages between this center and the rising power in Iran? Until Saddam Hussein’s fall in Iraq, a bequest worth “six million rupees” was credited to the Nawabs of Awadh for the upkeep of Shia shrines in Najaf and Karbala.

India’s charge d’affaires in Baghdad during the Saddam Hussein period, Rajendra Abhyankar, was among the last to operate the account by way of a stipend for Indian students at Najaf and Karbala.

After the fall of the Shah, Atal Behari Vajpayee and Jagat Mehta tossed a question at me: “Any possible links between Lucknow and the new rulers in Tehran?”

It turned out that there were links. Clerics from Lucknow had visited Khomeini in Najaf and, more recently, outside Paris. Indeed, Khomeini had very distinguished theological scholars as his ancestors from Kintoor. One of the lesser-known clerics, Agha Roohi Abaqati, was even related to Khomeini.

Abaqati became the peg around who, Mehta cobbled a high-powered delegation. The delegation was to be led by the socialist leader Ashoke Mehta. Badruddin Tayyabji was chosen for his flair. Abaqati would be an escort.

The Indian embassy in Tehran was alerted. Ayatollah Khomeini’s office at Jamaran, outside Tehran would receive the delegation. Between the interview being arranged and the actual arrival of the delegation, something quite unforeseen had happened.

Ambassador Ahuja was not in Tehran. It fell to the lot of Kuldip Sahdev to accompany the history-making delegation to the Ayatollah’s office.

What awaited the Indian delegation was a novel experience. What had emerged in Tehran had no parallel anywhere, except perhaps the Vatican, where the Pope rules supreme.

The delegation entered the hall where the Ayatollah sat at some distance. By a gentle gesture, Khomeini asked the delegation to wait near the entrance. He then asked an aide who wore a black turban and black gown to ask Abaqati to come closer.

Abaqati probably expected the founder of the Iranian revolution to hug him as a long-lost relative. What followed were fireworks. To the Indian delegation’s consternation, Khomeini gave Abaqati an earful.

The supreme leader was at his invective best. In deathly silence, the delegation walked backward towards the cars waiting for them. All meetings in Tehran were cancelled. They caught the earliest flight to Delhi in silence, chastened by an unexpected diplomatic reversal.

During a subsequent visit, an Ayatollah in Qom explained to me why the Abaqati initiative had collapsed.

“It is a vulnerable revolution with enemies in unexpected places.” That the leader of the Islamic revolution, which has upturned the power structure in a civilizational state, had “foreign roots” could be lethal ammunition in the hands of “our enemies”.

Abaqati was escorting the delegation on the strength of the fact that he was from a family of distinguished clerics from Kintoor and a chip of the same block as Imam Khomeini. This may have been the truth, but its amplification was anathema to the keepers of the revolution at this stage.

Later in India, something extraordinary happened at a reception hosted by Iran’s popular ambassador, Gholamreza Ansari. In his welcome speech, he dwelt at length on the civilizational ties between India and Iran.

“Even the leader of the Islamic revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini, had roots in India,” he said to a packed hall at the Leela hotel. Ambassador Ansari thought the tentativeness of the revolution’s earlier years “was a thing of the past”. The establishment in Tehran was now very secure.

Cultural links between the two civilizational states always remind me of Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee’s visit to Hafiz’s tomb in Shiraz. Adjacent to the tomb is a small library. On the cornice of the library is a remarkable photograph. During his visit to Iran, Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore made special arrangements to visit Hafiz’s tomb in Shiraz.

ALSO READ: Mohammad Hafeez Furqanabadi: Harbinger of education, harmony, social change

The photograph on the cornice shows Tagore going through the ritual of opening the “faal”. Open any page of a holy book or verses by a “seer” or a poet, and the first line is supposed to give you a clue to whatever you seek to know. It is not a matter of faith but poetic indulgence, an excuse to quote verse as a point of departure for a conversation.

The author is a veteran Journalist and author