Vidushi Gaur/ New Delhi

The new tricolour had barely risen before fires lit the sky. The cost of independence was being paid in homes broken, neighbours turned strangers, and streets where fear walked openly. Among the most anxious were the Muslim residents of the capital, suddenly unsure if the India they had chosen would still claim them.

In those first chaotic days, rumours spread that mobs were circling the precincts of the dargah of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, one of Delhi’s oldest spiritual sanctuaries, where generations of believers had come seeking comfort. But now, its courtyards were filled not with pilgrims, but with families clutching bundles of memories, praying for safety.

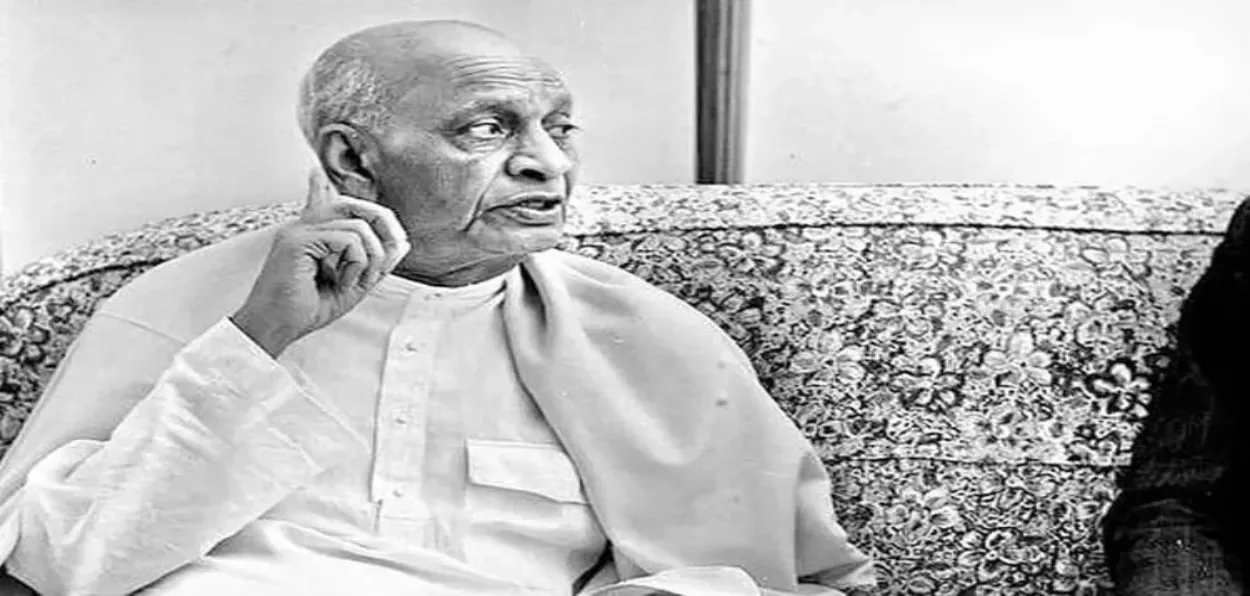

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the newly appointed Home Minister, heard the whispers. Many expected him to respond with a statement or a police memo. Instead, he got into his car.

Wrapped in a shawl, Patel walked quietly through the dargah gates. The crowd froze, unsure how the ‘Iron Man’ would react in a place that was the heart of Muslim devotion in Delhi. Patel did not speak at first. He offered a small gesture of respect at the tomb and then asked the caretakers about the residents, were they safe? Did they have food? Was anyone harmed?

When the senior police officer on duty approached, Patel’s voice hardened. If anything happened to the shrine or its people, he warned, the police would be held personally accountable. The state’s duty was not selective; its responsibility stood firm over every citizen’s right to worship, live, and hope.

Two years later, the Constituent Assembly chamber was calmer than the burning streets of 1947, but the wounds of Partition were far from healed. Debates around minority rights often reopened painful memories. Some voices questioned whether Muslims, who had become the “other” in the Partition narrative, deserved constitutional safeguards. Others argued that Pakistan’s creation had absolved India of responsibility toward its Muslim population.

It was here that Patel stood once again, firm but composed. He reminded the Assembly that millions of Muslims had refused to cross the border. They had placed their trust in India, not because of coercion or helplessness, but because India was their home. They had lived here for centuries, not as outsiders, but as builders of its culture, its cities, and its shared destiny.

Patel warned that treating them with suspicion or depriving them of participation would betray the moral foundation of the new nation. If India expected loyalty, it must first uphold equality. Citizenship could not be contingent on ancestry or religion. It had to be rooted in constitutional protection.

“We have assured them equal rights and opportunities,” he said in his unvarnished manner. “We must honour that pledge.”

He pressed for full Muslim representation in policing, administration, and public life, not as a concession but as a constitutional necessity. Security, after all, was not only about controlling violence but ensuring trust in the institutions that wielded power. A democracy where a large community felt alienated could not endure.

Therefore, his interventions helped shape policies that discouraged communal segregation in services and insisted on administrative impartiality. The Home Ministry under Patel pushed for rebuilding Muslim neighbourhoods, restoring properties, and reopening mosques, quiet acts of repair that were foundational to long-term national unity.

The dargah visit and the Constituent Assembly speech may seem different, one a midnight field intervention, the other a constitutional address, but they expressed the same principle: India had to be a nation where the Constitution, not religious identity, defined belonging.

Patel’s actions were not free of complexity. He was a man hardened by the trauma of Partition and wary of separatist politics. But precisely because he knew what division cost, he refused to let the new India be built on exclusion.

For him, protecting a Muslim shrine in chaos and demanding Muslim presence in policymaking two years later were interconnected duties. The first protected life; the second protected dignity. Standing in the shadow of Nizamuddin Auliya’s tomb, Patel had not simply promised protection; he performed it.

Many great decisions are remembered through documents and speeches. But some principles take shape in acts of presence, one leader showing up at a shrine under threat, affirming through his footsteps that a united India was not just an aspiration but a responsibility

ALSO READ: Was Sardar Patel biased against Muslims?

In that union of practice and policy, Patel revealed his answer to the central question of the time: Who belongs to India? His answer: “All who choose it and all whom the Constitution protects.”