Saniya Anjum

December 20 is observed globally as International Human Solidarity Day, to call attention to one of the most essential yet fragile values of our time: the idea that humanity is bound by shared responsibility, mutual respect, and moral obligation.

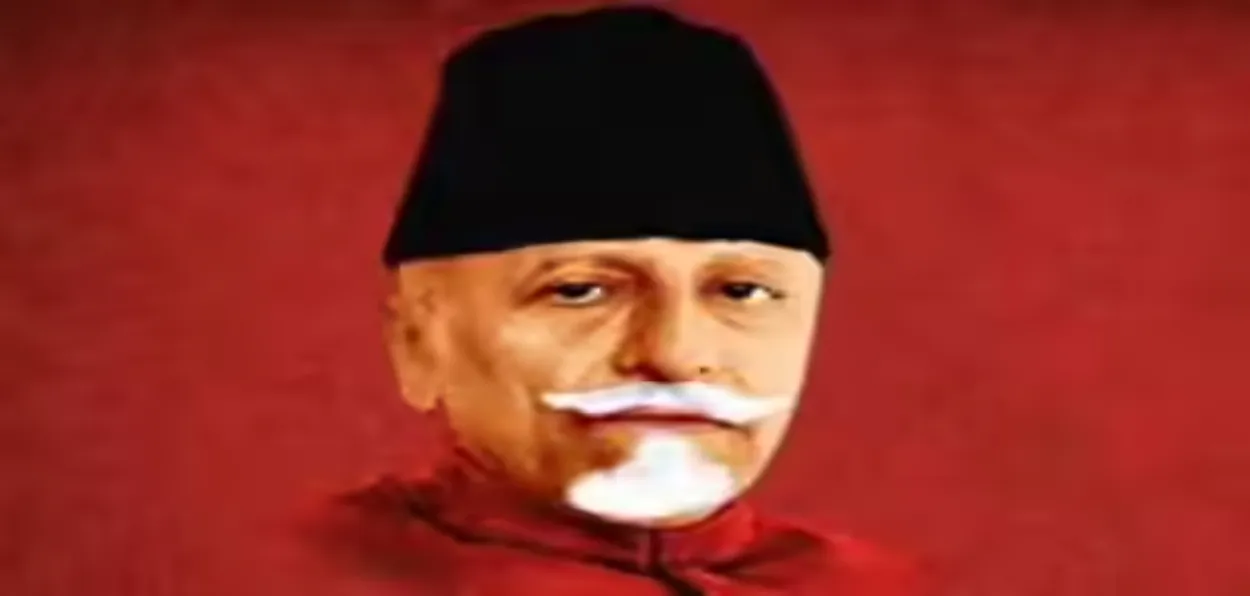

In an age of widening inequalities, ideological polarisation, and social fragmentation, the relevance of solidarity has never been more urgent. To understand what this principle truly means beyond slogans and declarations, one can look to the life and thought of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, a thinker, freedom fighter, and educationist whose ideas embodied solidarity not as a concept, but as a way of life.

Human solidarity is often spoken of in the language of international institutions, development goals, and humanitarian efforts. While these frameworks are important, solidarity ultimately begins at the level of human conscience. Abul Kalam Azad understood this deeply. For him, unity was not about uniformity, and coexistence was not about tolerance alone; it was about justice, dignity, and shared destiny. His vision offers a powerful lens through which December 20 can be meaningfully reflected upon.

Born in 1888, Azad emerged as one of the most influential intellectuals of India’s freedom movement. At a time when colonial rule thrived on division- religious, cultural, and political- Azad stood firmly for unity rooted in ethical responsibility. He believed that societies fracture not because people are different, but because they fail to recognise their interconnectedness. This belief aligns seamlessly with the spirit of Human Solidarity Day, which emphasises collective action in addressing global challenges such as poverty, exclusion, and conflict.

One of Azad’s most significant contributions to the idea of solidarity was his unwavering commitment to pluralism. He rejected the notion that identity must be singular or exclusive. In his writings and speeches, Azad consistently argued that religious and cultural diversity was not a weakness but a moral strength. Solidarity, in his view, meant standing with others not despite differences, but because of them. This perspective is particularly relevant today, when identity-based divisions continue to shape political and social discourse worldwide.

Azad also linked solidarity closely with education. As India’s first Minister of Education, he emphasised that knowledge must serve social harmony and human upliftment. Education, he believed, was not merely a tool for individual advancement but a means of building an informed, empathetic society. A society educated in this sense would naturally recognise injustice anywhere as a threat to justice everywhere. On December 20, when global institutions urge cooperation among nations, Azad’s emphasis on education as the foundation of solidarity feels especially instructive.

Another defining aspect of Azad’s philosophy was his insistence on moral courage. Solidarity, for him, was not passive sympathy but active responsibility. It required speaking out against injustice, even when doing so was uncomfortable or unpopular. During moments of communal tension and political uncertainty, Azad chose principle over expediency. His stance reminds us that solidarity is tested most severely during crises; precisely when silence feels safer than disagreement.

International Human Solidarity Day also highlights economic inequality and social exclusion. Azad’s thought anticipated this concern by stressing the ethical dimensions of governance and development. He believed that freedom without social justice was incomplete, and that political independence must translate into dignity for the most marginalised. Solidarity, therefore, was inseparable from accountability. It demanded that those with power recognise their responsibility toward those without it.

In a globalised world, where crises, climate change, pandemics, and displacement transcend national borders, the need for solidarity extends beyond communities and nations. Azad’s worldview, though shaped in a specific historical context, was inherently universal. He spoke of humanity as a moral community, bound by shared values rather than narrow interests. This universalism resonates strongly with the intent behind December 20: to reaffirm that global challenges require collective solutions.

As we observe Human Solidarity Day, it is worth asking uncomfortable but necessary questions. Are our commitments to solidarity reflected in our policies, institutions, and daily choices? Do we practice empathy only in moments of crisis, or do we embed it into the structures of society? Abul Kalam Azad’s life suggests that solidarity is not an occasional gesture but a sustained ethical practice.

December 20 should not remain a symbolic date on the calendar. It should serve as a reminder that solidarity is neither abstract nor optional; it is foundational to human progress. By revisiting the principles of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, we are reminded that true solidarity demands courage, inclusivity, education, and justice. In honouring this day, we are called not only to acknowledge our shared humanity but to protect and strengthen it actively.

ALSO READ: Ashhar-Anil dosti: A bond that transcends religions

As we reflect on December 20 and the meaning of human solidarity, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad’s words continue to offer quiet yet powerful guidance. He once said, “The world is divided into two camps: one of oppression and the other of resistance.” This reminder urges us to recognise where we stand, not as passive observers, but as participants in shaping a more just and compassionate world. True solidarity lies in choosing conscience over comfort, and humanity over division.