Amir Suhail Wani

Tucked into the Wangath-Gangabal side-valley above the Sindh River, about 15–20 km from Kangan in central Kashmir, Naranag is at once a quiet mountain hamlet, the gateway to one of Kashmir’s classic high-altitude treks, and the site of one of the valley’s most evocative archaeological ensembles — a cluster of eighth-century temple-ruins traditionally associated with Lord Shiva and the old Naga-Karkota rulers of Kashmir.

Though time and vegetation have reduced much of the complex to stone platforms and scattered pillars, the place retains a rare sense of continuity: pilgrims still pause here before heading up to Gangabal, shepherds graze nearby meadows, and trekkers set out from its fields toward the alpine lakes and Harmukh’s slopes.

The Naranag temple complex is commonly dated to the early medieval period of Kashmiri history, with several authors and local tradition crediting major construction to Lalitaditya Muktapida of the Karkota dynasty (8th century CE). Kalhana’s Rajatarangini and later histories record that the Wangath–Naranag area was a sacred circuit long before King Lalitaditya, with successive rulers (including Avantivarman) endowing and repairing shrines there.

The Naranag Spring

The layout — multiple shrines grouped around springs and platforms — reflects Kashmir’s medieval temple architecture and the regional pattern of royal sponsorship of Shaivite cult centres. Archaeological descriptions note square sanctums, strong granite blocks and carved portals typical of Kashmiri stonework of that era.

Naranag’s sanctity stems from two related strands of religious life. First, the site has long been identified with Shaivism: remnants of lingam worship and temple iconography at the complex point to its role as a Shiva shrine where devotees offered ritual bathing and puja.

Second, the name “Naranag” links it to the ancient Naga tradition (serpent-worship and ascetic Naga orders), a current that existed alongside mainstream Brahmanical Shaivism in early Kashmiri religiosity.

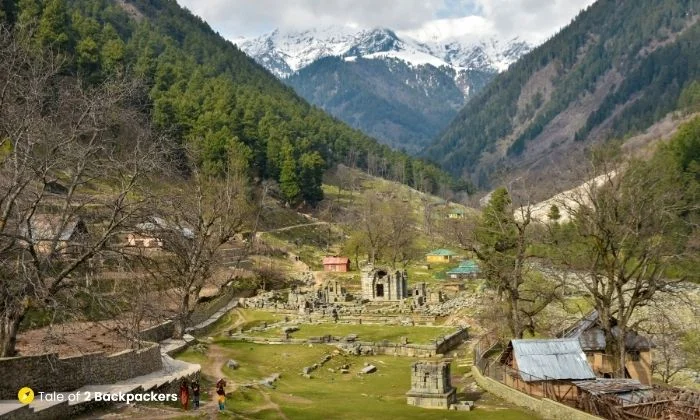

The Naranag temple Complex (Courtesy: Tale of two Bagpackers)

From a living-practice perspective, Naranag has been the traditional lower terminus for the annual pilgrimage to Gangabal and Nundkol — the twin alpine lakes under Harmukh — where Kashmiri Pandit pilgrims still perform rites in summer months. In short, Naranag forms part of a pilgrimage corridor that threads sacred springs, mountain lakes, and high pastures.

At its height, the complex comprised several stone temples clustered on terraces around a perennial spring; today, visitors find several platforms, pillared porches, a surviving sanctum or two and the scattered blocks of once-sculpted masonry.

The principal shrine — a compact, square sanctum with robust columns and an arched doorway — gives a clear glimpse of Kashmiri temple typology, where intricate stone-cutting and a preference for granite produced austere, geometric monuments that weathered mountain winters.

Conservation efforts have stabilised parts of the site and a perimeter has been built in places, but much remains exposed and vulnerable to seasonal growth, frost action and human pressure. Descriptive accounts emphasise both the elegance of the surviving architecture and the melancholic air of a once-grand ritual centre now half-reclaimed by meadow and forest.

Naranag is not a museum isolated from daily life — it is embedded in a pastoral and agrarian landscape. Local shepherds and Gujjar communities use the surrounding meadows; villagers maintain small orchards and fields lower down the valley. The cultural life of the area mixes Muslim village traditions with the residual memory of pre-modern Kashmiri Hindu pilgrimage practices: in summer months, small groups of Kashmiri Pandits still walk the trail to Gangabal, stopping at Naranag to offer prayers and mark the start of the ascent.

The Gangbal lake

Modern visitors — trekkers, photographers and a rising number of domestic tourists — have made the hamlet a seasonal meeting point where local hospitality (simple tea-huts, homestays) meets mountaineering logistics.

For trekkers and nature-lovers, Naranag’s importance is practical as well as poetic: it’s the usual base for the two-to-three-day Naranag–Trundkhol–Gangabal trek that climbs through pine forests and alpine meadows to the twin lakes beneath Mount Harmukh. The route is prized for its scenery — thick conifer slopes, wide highland bowls, and dramatic lake basins — and for the way it layers archaeology, faith and wilderness into a single itinerary.

Local guides and trekking operators run packages from Srinagar and Kangan, and the walk remains one of Kashmir’s classic summer treks.

Despite its importance, Naranag faces conservation and infrastructure challenges. The remoteness that protects its ambience also exposes the ruins to weathering, vegetation overgrowth and occasional theft or damage. Mobile connectivity has historically been poor, complicating tourism management and emergency response.

At the same time, modest growth in visitor numbers and social media attention places new pressures on fragile stonework and fragile mountain ecosystems. Local authorities and heritage advocates have undertaken limited protective measures, but many experts call for a coordinated conservation plan that balances pilgrimage, trekking tourism and archaeological preservation.

Naranag’s value is not limited to a single domain. Historically it is a marker of Kashmir’s medieval polity and temple-building patronage; religiously it is part of a living sacred geography that links valley communities with high-lake shrines; culturally and socially it is a place where pastoral life, village routine and seasonal pilgrimage intersect; and for visitors it is a rare spot where an archaeological site sits within an active mountain landscape rather than behind glass. Visiting

ALSO READ: Mahmud Akram: the boy who knows 400 languages

Naranag is, thereforeboth an encounter with stone and a meeting with the layered human memories that make Kashmir’s valleys legible across time.