Saquib Salim

Saquib Salim

Given the high temperatures of political circles in the country, it will be difficult for one to believe that Vande Mataram was sung at the start of public meetings during the Khilafat Movement, an agitation to save the Islamic Caliph of Turkey, during the 1920s.

A CID report from 24 January 1920, records a visit of Mahatma Gandhi in Meerut with these words, “Mr Gandhi arrived in Meerut at 9.30 by motor car and received a rousing welcome by a large crowd which was awaiting his arrival at the Devanagri School….. The volunteers were divided into various crops, emblematic of (1) Egypt, (2) Arabia, (3) Turkey, and these youths were wearing uniforms representing these various countries. The crescent was universally worn. There was a special body of volunteers styled Gandhi-ki-fauj……. It is worth noting that the Muhammadan volunteers were all wearing the yellow ochre (chandan) on their foreheads….. The other address was read in English by Pandit Ghasi Ram, M.A., and in Urdu by Muhammad Aslam Saifi. Two poems were also recited. The national song Bande Mataram was sung by four Bengalis.”

The meeting was part of the Khilafat Movement and had a majority of Muslims. This was no one-off event. Another CID report from 22 April 1920 recorded a meeting of Shaukat Ali as, “On the 14th April, Maulana Shaukat Ali and his two supporters from Sind held a meeting in the Idgah compound, Sholapur, under the auspices of the local Khilafat Committee……. After several religious songs and Bande Mataram the address was read out in English by a butcher of Bijapur. It was then translated into Urdu by Abdul Haq Abdul Rajak (President, Sholapur Khilafat Committee) and into Marathi by J. M. Samant, Pleader, both of Sholapur. Its purport was that Shaukat Ali and his brother Mahomed Ali had revivified the political life of Moslems in India.”

In fact during Khilafat Movement, Shaukat Ali suggested to Mahatma Gandhi, “There should be therefore only three cries recognised: 'Allaho Akbar', to be joyously sung out by Hindus and Muslims, showing that God alone was great and no other; the second should be 'Bande Mataram' (Hail Motherland) or 'Bharat Mata ki jai’ (Victory Mother Hind). The third should be 'Hindu-Musalman ki jai', without which there was no victory for India and no true demonstration of the greatness of God.”

It is often argued that Muslims in India had problems with Vande Matram from the very beginning. But these CID reports, and reports prove that the song was being sung during the Muslim dominated Khilafat Movement. The Ali Brothers themselves raised the slogans.

A few scholars have written that the first major opposition to Vande Mataram, calling it a Hindu song, came from Maulana Muhammad Ali during the 1923 Kakinada Congress Session. Was it so?

Muhammad Ali was the president of this Congress Session. Another freedom fighter, Asaf Ali, wrote about the incident, “The renowned musician (Pandit Vishnu Digambar Pulaskar) was present at the session and was invited to sing the national song, 'Vande Mataram”. Mohammad Ali, who was in the chair, objected on the grounds that music was taboo to his religion. The leaders assembled were completely bewildered. Vishnu Digambar was incensed and hit back: ‘This is a national forum, not the platform of any single community. This is no mosque, to object to music... When the President could put up with music in the presidential procession, why does he object to it here?’ Having silenced the President… he proceeded to sing Vande Mataram and completed it.”

The objection raised by Muhammad Ali was not to Vande Mataram as a Hindu hymn but to the music, which, according to him, was forbidden in Islam. Though he was convinced by Pulaskar and stood with all others present when Vande Mataram was sung.

Interestingly, Muhammad Ali was present with his wife, Amjadi Begum, and his brother Shaukat Ali at the Belgaum Congress Session next year too, where the proceedings were started by Gangu Bai Hangal with the singing of Vande Mataram. Hundreds of Muslims, including Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, were present.

When did it turn into a controversy? In 1935, The Hindustan Times leaked a government circular to check the singing of Vande Mataram at public events. The British government had to step back. The archival files reveal that the officials suggested to popularise among Muslims a view that Anandmath, the novel in which this song was featured, had anti-Muslim overtones. Though British officials agreed that there was nothing objectionable in the song, Muslims should be told that this was a Hindu hymn.

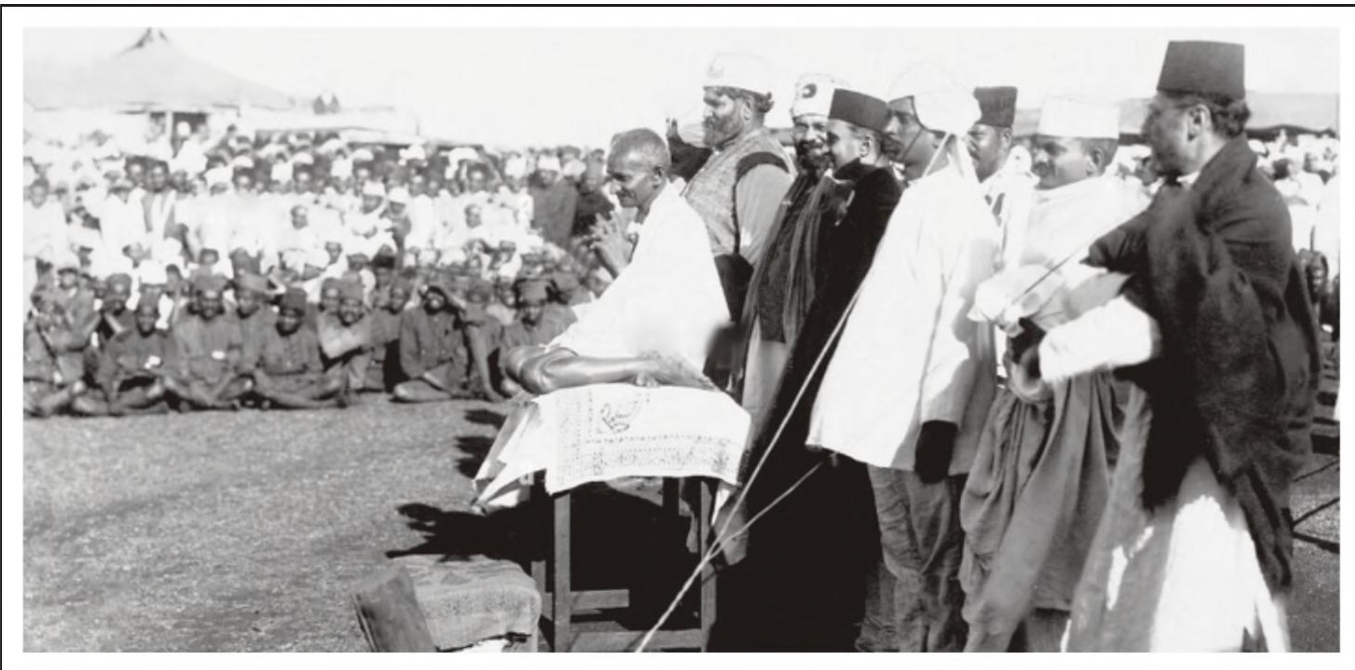

Mahatma Gandhi with Mohammad Ali and Shaukat Ali at the Belgaum session of Congress in 1924

After the provincial governments led by Congress were formed in several provinces, on 17 August 1937, the Viceroy wrote to the Governor of Bombay in an alarming tone, “The essential basis of objection to it (Vande Mataram) has been its former associations with extremism, which may be regarded as having ceased to be of immediate material importance. The position is complicated by the fact that “Bande Mataram” has now been sung in Provincial Assemblies in two or three of the Congress Provinces and that, I understand from press reports, in at least two Provinces the whole Assembly, including the European group, etc., has stood while it was being sung. My own view is very strongly that we should be very ill-advised to allow the question of our attitude towards the singing of this song to develop into a major political issue and that were we to do so we should merely play into the hands of the Left Wing by creating trouble over a matter which is of no substantial intrinsic importance.... But I am disposed to see strong objection, subject to this, to any recognition of this song as a see strong objection, subject to this, to any recognition of this song as a “National" song or anthem and in my opinion we should regard it merely as a patriotic song and justify our action in standing during its singing on grounds of general courtesy and consideration for the feelings of those present.”

Who would come to help the British in this crisis? Of course, the Muslim League and Mohammad Ali Jinnah! He raised an issue around Vande Mataram. Viceroy Linlithgow wrote to the Secretary Zetland on 27 October 1937, “As you will probably have gathered from the reports, a considerable Muslim agitation has developed against the use of “Bande Matram', as a “National' anthem and resolutions on the subject have been passed at the recent Muslim League Conference. That is all to the good from our point of view, for it is clearly preferable that the pressure should come from independent quarters rather than from Government, and I am glad to think that the Muslims should appear to be waking up to the significance of the song, given its history, from their point of view. I am not without hope that a somewhat similar situation will shortly develop regarding the Congress flag.”

It must be kept in mind that, according to the statement released by the AICC Working Committee on 28 October 1937, a Muslim played an important role in elevating Vande Mataram to the pedestal of a revolutionary national song. The statement said, “At a session of the Bengal Provincial Conference held in Barisal in April 1906, under the Presidentship of Shri A. Rasul, a brutal lathi charge was made by the police on the delegates and volunteers and the Bande Matram badges worn by them were violently torn off. Some delegates were beaten so severely as they cried Bande Mataram that they fell senseless. Since then, during the past thirty years, innumerable instances of sacrifice and suffering all over the country have been associated with Bande Mataram and men and women have not hesitated to face death even with that cry on their lips. The song and the words thus became symbols of national resistance to British imperialism in Bengal, especially, and generally in other parts of India.”

The Congress committee was formed, including Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, which said that there is nothing anti-Muslim or pro-Hindu in the first two stanzas of the song. Why only the first two stanzas? The working committee said, “Gradually, the use of the first two stanzas of the song spread to other provinces, and a certain national significance began to attach to them. The rest of the song was very seldom used and is even now known by few persons. These two stanzas described in tender language the beauty of the motherland and the abundance of her gifts. There was absolutely nothing in them to which objection would be taken from the religious or any other point of view.”

Jawaharlal Nehru said on 30 October 1937, “At the same time we have tried to point out that a part of the song, the first two stanzas, is such that no one can take objection to, unless he is maliciously inclined.”

Rafi Ahmad Kidwai, on 19 October 1937, alleged, “Mr Jinnah characterises Vande Mataram as an anti-Islamic song. Mr Jinnah had been a devoted and enthusiastic member of the Congress and of its chief executive, the All-India Congress Committee, for a number of years. Every year, the session of the Congress opened with the singing of this song, and every year he was seen on the platform listening to the song with the attention of a devotee. Did he ever protest? Mr Jinnah left the Congress, not because he thought the Vande Mataram was an anti-Islamic song, but because he was opposed to the change of creed that was made at the Nagpur Congress, which was defined as the attainment of Swaraj instead of Dominion Status.”

A reading of historical records shows that the controversy around Vande Mataram arose only after 1935, when the British Government wanted t test its popularity without introducing any law.

ALSO READ: Jinnah raised Vande Mataram controversy for political reasons

The Muslim League rallied people, claiming that the song is anti-Islamic. Hakim Ajmal Khan, M. A. Ansari, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Ali Brothers, Amjadi Begum, Bi Amma, Hasrat Mohani, Saifuddin Kitchlew, etc. didn't become lesser Muslims because they attended all the Congress sessions where Vande Mataram was recited.