Sabiha Fathima Begum

Some stories are not meant to entertain. They are meant to disturb, to question, and to stay with you long after the screen fades to black. The Shah Bano case is one such story — not merely a legal battle, but a moral reckoning for a nation caught between faith, law, politics, and human dignity.

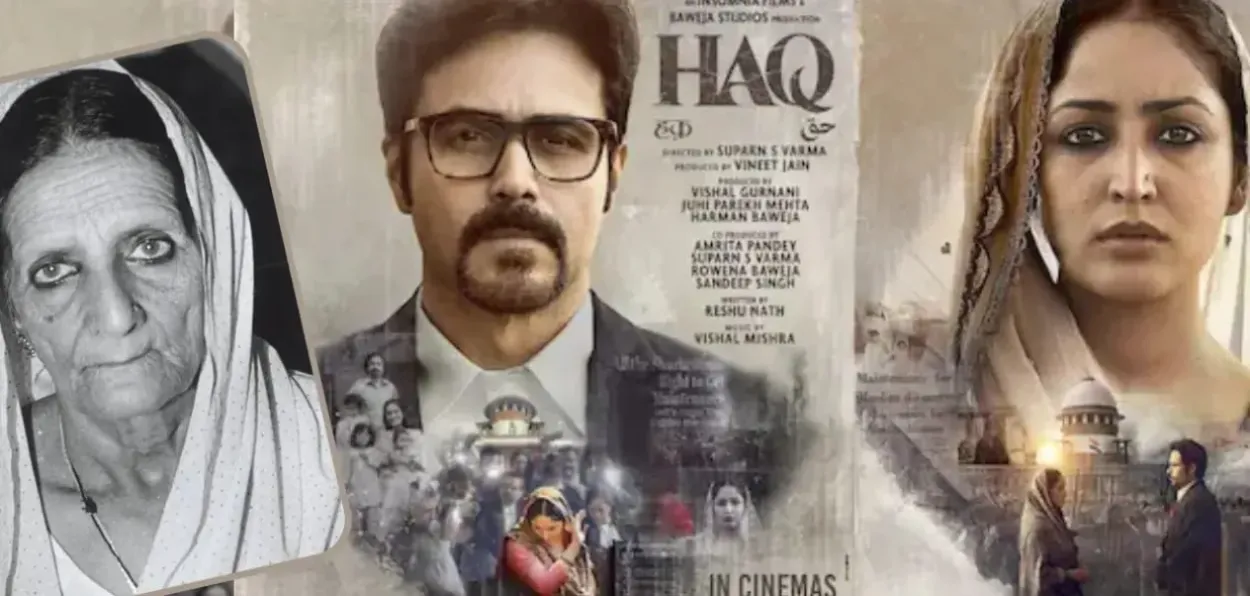

When cinema revisits this history, stitched together with courtroom speeches, Quranic verses, and anguished monologues about identity and belonging, it becomes more than a film. Haq featuring Yami Gautam in one her best performance so far and Imran Hashmi becomes a mirror.

At the heart of this narrative lies a simple yet devastating truth: sometimes justice is not denied by cruelty, but by compromise. “Kabhi kabhi mohabbat kaafi nahi hoti, humein izzat bhi chahiye.” (Sometimes love is not enough — we need dignity). This dialogue by Shazia Bano played by Yami Gautam, is about a hurt felt by a woman at her man’s treachery cloaked in religion.

Though the filmmaker has not linked the film to the Shah Bano case, the connection is apparent to those who know about the fight of a Muslim woman for her dignity after being abandoned by her husband for another woman. The above dialouge alone captures Shazia Bano’s struggle. She was not fighting religion; she was fighting abandonment.

An elderly woman, married for over 40 years, thrown out of her home, divorced through triple talaq, and denied even basic financial support — Shah Bano’s tragedy was heartbreakingly ordinary. What made it extraordinary was her courage to walk into a court of law and ask for ₹500 a month under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code. Not as a rebel or reformer, but as a hungry, helpless woman asking not to be left to die quietly.

And suddenly, a personal plea turned into a national storm.

The film’s courtroom speeches — especially those echoing Imran Hashmi’s lines — expose a deeper anxiety within Indian Muslim identity: “Yeh case sirf maintenance ka nahi hai… yeh case hai musalman ki pehchaan ka.” (This is not just about maintenance; this is about Muslim identity).

For decades, Indian Muslims had already paid a heavy price for Partition — blamed for a division they did not choose, repeatedly asked to prove loyalty to a nation they never left. In this fragile atmosphere, the Shah Bano judgment felt, to many, like another stripping away — not of money, but of autonomy.

The fear was not about ₹500. The fear was: If secular law can override Muslim personal law here, what remains of our distinctiveness? Thus the debate hardened into binaries -Personal Law vs Secular Law; Identity vs Equality; Community autonomy vs Women’s rights

But the film and history both reveal i that this was never truly a clash between Islam and justice. It was a clash between power and vulnerability. Because the Quran itself says: “Walil mutallaqati mata’un bil ma’roof” — Divorced women must be provided for with fairness. Sharia does not preach abandonment. It condemns it.

Yet somewhere between scripture and social practice, compassion was replaced by control. The Supreme Court’s 1985 judgment in Mohd. Ahmed Khan v. Shah Bano Begum remains one of the boldest moments in Indian legal history. It said clearly:

Earlier cases like Bai Tahira (1978) and Fuzlunbi (1980) had already paved the way, affirming that Muslim husbands could not escape responsibility by paying token mahr and washing their hands of a woman’s survival. The courts were doing what law is meant to do at its best — protect the weakest.

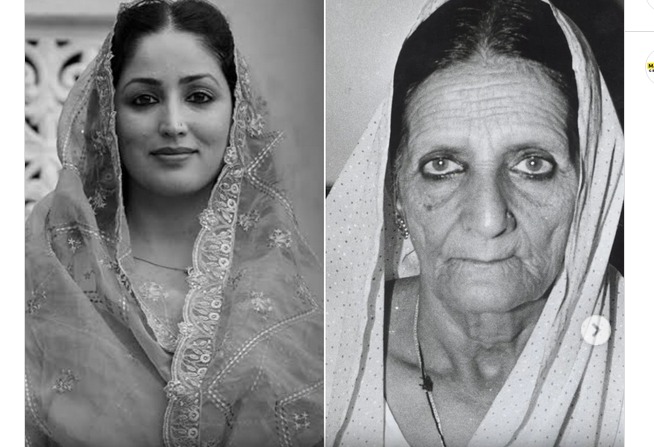

Shazia Bano in Haq (Yami Gautam) and late Shah Bano

But justice in a courtroom does not always survive politics outside it.

The tragedy deepened in 1986 when the Rajiv Gandhi government, bowing to pressure from conservative religious leaders, passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act. Overnight, Shah Bano’s victory was hollowed out. Maintenance was limited to the iddat period. What the Supreme Court had given, Parliament took away.

The film captures this betrayal with painful clarity: “Secularism ke naam par humse wada khilafi ki ja rahi hai.”In the name of secularism, promises are being broken.

Shazia, like real-life Shah Bano, becomes the casualty of vote-bank politics — her dignity traded for political convenience. The same leaders who claimed to protect Muslim identity ended up sacrificing a Muslim woman’s life to do so.

While the nation debated her case in drawing rooms and parliament halls, Shah Bano was isolated, pressured, and accused of dishonouring Islam. She received threats. She was asked to withdraw.

Though the law eventually turned against her, the greater tragedy was personal. Shah Bano was left carrying the burden of a national debate on her fragile shoulders. Facing social pressure and public scrutiny, she chose silence over struggle — not as a defeat of faith in justice, but as a quiet search for peace after years of conflict.

Imran Hashmi who plays a wealthy lawyer husband of Shazia Bano in a court scene

She once said, in essence: “I wanted dignity, not a movement.”And yet, she became a movement. What the film does beautifully is what judgments often cannot — it restores the human face to a legal citation.

The speeches by characters echo the anguish of a community torn between survival and self-respect, but the camera never lets us forget the woman at the centre.

Shazia Bano’s dialouge “Talaq ek gaali ban chuka ha,” Divorce has become a curse word, reminding us that behind every ideological debate is a woman paying the price. And when another voice argues that nikah is not just a contract but a responsibility, the film quietly asks: if faith cannot protect the vulnerable, what is it protecting?

In 2001, long after Shah Bano’s death, the Supreme Court reinterpreted the 1986 law and restored what it had always meant: Muslim women are entitled to a fair and reasonable provision for life.

This film and Shah Bano’s narrative are not relics of the past. They speak directly to today’s India, where questions of Uniform Civil Code, religious freedom, and women’s rights still ignite the same anxieties.

Happily married couple (Scene from Haq)

But the lesson is timeless: A nation is not judged by how loudly it protects traditions, but by how quietly it protects its most vulnerable citizens.

Through her courtroom battle, she raised an uncomfortable question: Can a society claim moral greatness if it sacrifices women at the altar of identity?

What deserves special recognition in this entire saga is the moral courage shown by the Indian judiciary. From Bai Tahira to Fuzlunbi and finally Shah Bano, the courts consistently refused to reduce Muslim identity to a rigid stereotype. Instead of seeing secular law as an enemy of faith, the judges treated it as a bridge, proving that constitutional values and religious conscience need not be rivals.

By upholding maintenance rights, the Supreme Court did not attack Islam; it protected the most humane spirit within it. In doing so, the judiciary preserved not only the dignity of divorced Muslim women, but also the dignity of Indian Muslim identity itself — showing the nation that justice strengthens a community, it does not erase it.

ALSO READ: INA represented the real idea of secular India

This is not just a film review, but a reminder.

The Shah Bano story, told through cinema and history, is not about law versus religion. It is about courage versus comfort, justice versus convenience. She never asked to be a symbol. She only asked not to be abandoned. And because she refused to disappear quietly, India was forced — however reluctantly — to listen. That is her legacy.