Atir Khan

Atir Khan

The story of Hindu–Muslim polarisation in modern India cannot be understood without revisiting the Khilafat Movement of the early twentieth century. More than a protest against British policy, it marked the first large-scale mobilisation of Muslim religious identity in mass politics.

Its consequences reshaped political consciousness in ways that continued to reverberate long after the movement itself collapsed. For centuries before British rule consolidated itself, Muslim political authority in India had adapted to demographic reality.

The Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughal Empire governed a Hindu-majority society and could not sustain a strictly theological state. Political survival required accommodation.

Sharia was never uniformly enforced across the subcontinent; local customs endured, Hindu elites retained influence, and governance evolved through negotiation rather than doctrinal imposition.

There were excesses, but in personal matters, different communities were often governed by their own customary laws. Religious identities, though distinct, were not yet organised into watertight political blocs. Syncretism was indeed less an idealistic project than a pragmatic necessity.

This equilibrium was disrupted not by medieval Muslim rulers but by colonial transformation. With the decline of Mughal authority and the consolidation of British power, Muslim political elites and the ulema lost institutional dominance.

A community that had once exercised sovereignty now faced marginalisation under a foreign empire. At the same time, new administrative and educational systems rewarded those who adapted quickly to colonial modernity. The transition generated insecurity among the Muslims, and insecurity often seeks symbols.

The Khilafat question became such a symbol.

After the First World War, the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire and the perceived threat to the Caliphate resonated deeply among many Indian Muslims.

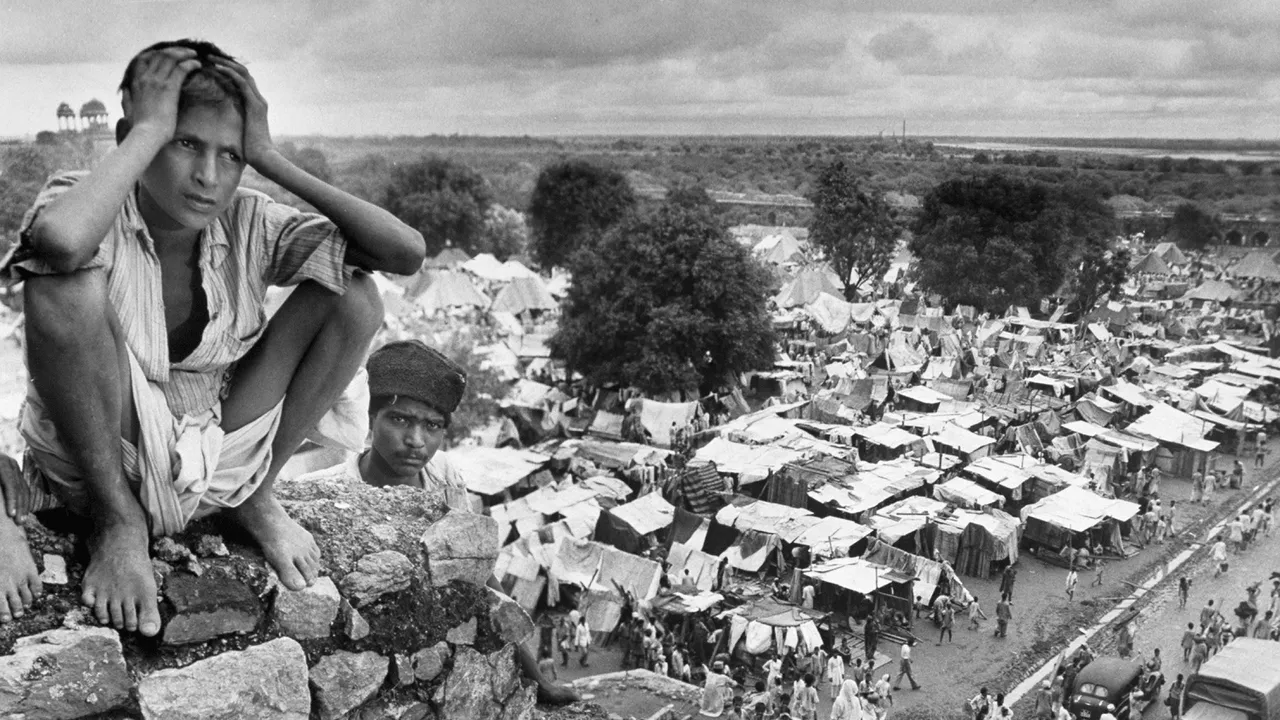

A Scene from a refugee camp in Delhi after the partition

A Scene from a refugee camp in Delhi after the partition

Although geographically distant, the Ottoman Sultan was regarded by sections of the Muslim world as a symbolic guardian of the Ummah and custodian of Islam’s holy sites in Arabia. Defence of the Caliph fused religious sentiment with anti-colonial politics in India.

It became a rallying point, and the movement also drew energy from earlier developments. Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s Aligarh Movement had already emphasised Muslim distinctiveness, which later transpired into a two-nation theory in colonial India.

The Balkan Wars of 1912–13 stirred pan-Islamic sympathy. Local communal tensions, such as the Kanpur riots and colonial census and classification policies, further sharpened identity boundaries.

By the time the Khilafat agitation gained momentum in 1919, the ground had been prepared for a mass appeal rooted in religious solidarity.

For the first time in modern Indian history, large sections of Muslims across regions mobilised around a shared religious-political cause.

A scene of Hindu Muslim brotherhood

The movement was led prominently by ulema and figures such as the Ali brothers.

Historian Mushirul Hasan observed that the Khilafat campaign, rooted partly in a romanticised vision of pan-Islamic unity, also marked a milestone in the evolution of a distinct Muslim political consciousness.

Mahatma Gandhi supported the movement, hoping that Hindu–Muslim unity would strengthen the broader struggle against British rule. For a brief moment, religious mobilisation and anti-colonial nationalism in a unique and extraordinary development marched together.

Yet the alliance proved fragile. Gandhi withdrew the Non-Cooperation Movement and his support to the Khilafat movement. In 1924, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk formally abolished the Caliphate in Turkey. The Khilafat Movement rapidly dissolved.

However, the political energy it had unleashed did not simply disappear.

The collapse of the movement acted like a breach in an embankment: once mass religious mobilisation had entered the grammar of politics, it could not easily be contained. Political identity organised around faith rarely retreats quietly.

Colonial policies such as separate electorates and communal representation further hardened boundaries.

A scene of Hindu-Muslim unity in india

A scene of Hindu-Muslim unity in india

The British did not invent religious identities, but administrative frameworks increasingly treated Hindus and Muslims as homogeneous and yet different political blocs.

As historian Dominique-Sila Khan has argued, colonial systems of classification reshaped how religion was conceptualised in India. Administrators often worked within simplified categories — a singular “Hinduism” and a singular “Islam” — flattening internally diverse traditions into political abstractions.

Over time, Hindu and Muslim leaders negotiated power less as citizens within a shared polity and more as representatives of distinct communities.In northern India, particularly in the United Provinces, sections of Muslim elites articulated demands for constitutional safeguards and privileges.

Intellectual currents from Aligarh, the poetry of Allama Iqbal, and later the leadership of Muhammad Ali Jinnah transformed minority anxiety into structured political claims powered by a superiority complex.

It is a known fact that not all Muslims supported Partition — certain Ulema from Deoband, leaders such as Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, argued forcefully for composite nationalism — yet the logic of separate political identity had gained powerful momentum, which could not be stopped.

Polarisation, however, rarely moves in only one direction. Muslim political consolidation generated strong parallel currents within sections of Hindu society.

ہندو مسلم پولرائزیشن کی جڑیںhttps://t.co/E5i175Y60n#india #muslim #HinduMuslim pic.twitter.com/IwHC0algRW

— Awaz-The Voice URDU اردو (@AwazTheVoiceUrd) February 15, 2026

The British assigned separate personal laws to both Hindus and Muslims.

Hindu reformist and revivalist movements, and eventually political organisations grounded in Hindu identity, emerged partly in response to perceived communal bargaining by the Muslims.

Between 1885 and 1947 — scarcely six decades — a fragile accommodation that had evolved over centuries fractured catastrophically, culminating in the Partition, which was followed by unprecedented violence.

Independent India adopted constitutional secularism in an effort to transcend this rupture. Muslim members in the Constituent Assembly reciprocated and volunteered not to opt for Muslim reservation.

Over a period of time, religious polarisation has intensified. Historical anxieties do not vanish easily. Periods of mistrust re-emerge when communities retreat into grievance and memory. When insecurity shapes political mobilisation, cycles of reaction and counter-reaction follow.

The Khilafat Movement’s significance lies not in assigning singular blame but in understanding precedent.

It demonstrated how mass politics anchored primarily in religious identity — even when driven by anti-colonial aspirations — can permanently alter the structure of public life.

Once faith becomes a central axis of mobilisation, compromise grows harder and suspicion easier.

What is certain is that political maturity, not romantic nostalgia or reactive grievance, determines whether plural societies endure.

ALSO READ: New Delhi and Dhaka can reset ties after BNP's victory

Civilisations are inherently syncretic. Attempts to recast them through singular identities — religious or otherwise — carry consequences that history repeatedly warns against.

The author is the Editor-in-Chief of Awaz-the Voice portal