Kolkata

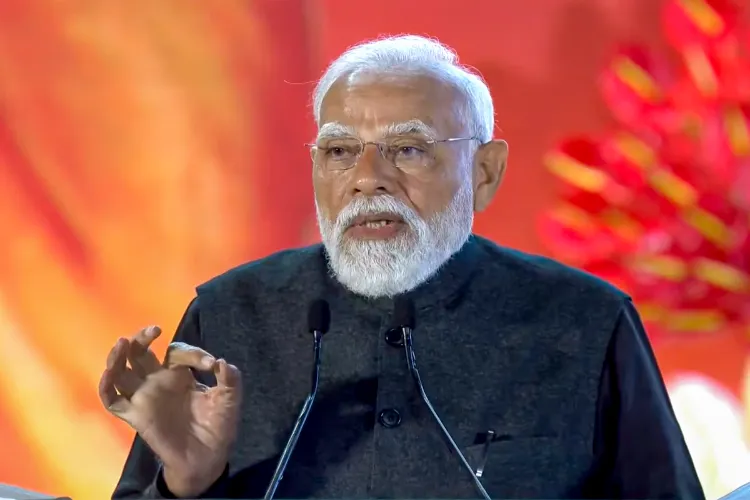

West Bengal’s political discourse appears to have come a full circle, with the BJP selecting the erstwhile Tata Nano factory site in Singur for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s rally on January 18, a move aimed at reviving debate around the state’s stalled industrial journey and lost economic opportunities.

By choosing the symbolically charged Singur ground in Hooghly district, the BJP is seeking to sharpen its campaign narrative against the ruling Trinamool Congress (TMC), banking on the enduring perception that Bengal has struggled to attract large investments since Tata Motors exited the small car project over a decade ago.

As the party prepares to step up its poll outreach ahead of the assembly elections, BJP leaders hope Modi’s address will lay out a broad roadmap for industrial revival in the state, while underscoring what they describe as the TMC government’s failure to reverse Bengal’s industry-starved image.

Party leaders believe the venue itself reinforces their message. The abandoned Nano site, months ahead of the polls, is being projected as a reminder of what the BJP calls missed opportunities under successive regimes and a platform to present its alternative vision for economic revival.

State BJP president Samik Bhattacharya told PTI that the Singur land has little agricultural value today, as its character was altered long ago for industrial use. “West Bengal needs a comprehensive land policy to attract heavy industry. That is the only sustainable way to retain talent and curb brain drain and forced migration,” he said.

Bhattacharya argued that farmers should be made direct stakeholders in industrial projects that require land, rejecting Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee’s emphasis on what she terms agriculture-industry coexistence. “With 82 per cent of land in Bengal held by small farmers, large industrial projects inevitably require agricultural land,” he added.

Highlighting the state’s geographical advantages, Bhattacharya said Bengal’s rivers, coastline and proximity to mineral-rich states could make it attractive to investors, provided institutional safeguards are strengthened. “Investors also need confidence that the lower judiciary functions free of political influence and ensures fair adjudication in business disputes,” he said.

Singur became a flashpoint in 2008 after widespread protests, spearheaded by the then opposition TMC, against the Left Front government’s acquisition of fertile farmland for the Tata Nano project. The agitation, marked by violence and clashes, ultimately led Tata Motors to abandon the project and relocate it to Gujarat, then governed by Modi.

At the time, an anguished Ratan Tata had publicly blamed Banerjee for the project’s collapse, remarking that she had “pulled the trigger” that forced his company’s exit.

The Singur episode proved to be a turning point in Bengal’s political and industrial history. While it helped Banerjee end the Left’s 34-year rule and ascend to power in 2011, it also left the state grappling with a reputation for being hostile to industry.

Economist and BJP MLA Ashok Lahiri said reviving agriculture on the Singur plot was never a viable option after the land-use change. However, he cautioned that giving equity stakes to landowners could be complex. “A more practical model would be for small farmers to pool land through cooperatives or companies and lease or sell consolidated parcels to investors,” he suggested.

The TMC, which has dominated Singur’s electoral landscape for over two decades, has brushed aside the renewed spotlight on the site. State minister Chandrima Bhattacharya recently said the Supreme Court had ruled the Singur land acquisition illegal. “Where were these leaders when farmers were beaten and their land forcibly taken?” she asked.

CPI(M) leader Srijan Bhattacharya, who contested Singur unsuccessfully in 2021, said fragmented landholdings have limited agricultural sustainability and that land acquisition for industry must be handled sensitively. “Owners must be taken into confidence, given adequate compensation and assured rehabilitation,” he said, while questioning the BJP’s credibility for supporting Banerjee’s agitation during the Singur protests.

Industry insiders, meanwhile, said Singur was not the sole factor dampening investor sentiment. They pointed to a March 2025 law enacted by the TMC government that retrospectively withdrew industrial incentives promised since 1993, citing fiscal constraints.

ALSO READ: What do Quran, Hadith, and Caliphs mandate about Illegal religious structures?

“Unless this issue is addressed, rebuilding investor confidence will remain difficult, especially for companies already hit by policy reversals,” an entrepreneur said on condition of anonymity.

The TMC, however, maintains that Bengal’s industrial health remains robust. In its pre-election performance report, the government claimed the state ranks among the top in company registrations and recorded an average profit growth of 546 per cent per factory between 2011 and 2024.