Atir Khan

Atir Khan

This topic is so vast that even a lifetime of scholarship would hardly be enough to fully understand and appreciate its full scope, depth, and richness.

Let us begin with Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal Emperor, who was exiled to Rangoon. He wrote the famous couplet: Kitna hai badnaseeb Zafar Dafan ke liye Do gaz zameen bhi na miliku-e-yaar mein…

For any Muslim, the choice of a final resting place is deeply emotional. Zafar mourns that he could not be buried in his beloved Delhi. This verse captures the emotional and civilisational strength of India's inclusive spirit. An Indian Muslim born in India would always wish that to be buried here.

The Awaz Commentary

This country has always valued human dignity over material concerns. Countless people from all parts of the world down the ages chose India to make their home—for unparallel peace of mind, spiritual depth, and innate humanity it offers.

As the sun sets, the winter smog descends over ponds of North Indian Villages and it is time for cooking, heating of mustard oil is similar in all the kitchens, irrespective of whether it belongs to a Hindu or a Muslim.

Inclusive Raksha Bandhan at Agra

The mingling sounds of aarti and azan in Benaras, or temples, mosques, churches and gurdwaras coexist peacefully in Chandni Chowk— are living symbols of civilisational harmony.

The Indians embrace Shah Rukh Khan as Mohan Bhargava in Swades, and Ajay Devgn as football coach Syed Abdul Rahim in the film Maidan. And why Indians love Mohammad Rafi’s bhajan “Man Tadpat Hari Darshan ko Aaj,” which he sung in rag Mallkus in feature film Baiju Bajwa in 1952.

India’s inclusiveness survives not merely in history books but in everyday gestures even today. For example:

• In Uttarakhand’s Kashipur, Hindu sisters Saroj and Anita donated land for an Eidgah.

• In Ayodhya, Hindus donated land for a Muslim kabristan.

• In Jammu, when the home of a Muslim journalist was demolished, Hindu neighbour generously gifts hisland to help him rebuild his house.

• In Assam’s Bongaigaon, Ratikanta Choudhury donated land to build a road to the local mosque.

• In Kerala, a Muslim Jamaat donated land for a Ganesh temple—and children from both communities joined the Pran Pratishtha procession.

• In Dehradun, Sushma Uniyal and Sultana Ali exchanged kidneys to save their husbands’ lives.

• Faisal took a plunge in the river to save drowning Shubham in Pilibhit.

These examples clearly show that Indians even today don’t hesitate to make sacrifices for each other, even if comes to risking their lives.

M. Mujeeb in his fascinating book The Indian Muslims reveals how deeply entwined Hindu–Muslim cultures were—well into the 19th century:

• In Karnal, Muslim agriculturists worshipped village deities while reciting the Kalimah.

• Meos and Minas of Alwar and Bharatpur celebrated Diwali, Dussehra, and Janmashtami.

• In Purnea, Bihar, Muslim households kept shrines where Allah and Kali were invoked together.

• In Kishanganj, shrines of Baishahari—the snake goddess—stood alongside mosques.

• Hussaini Brahmins observed Ramzan while remaining devotees of Imam Hussain.

• In Ahmedabad, Shaikhs wore tilak but buried their dead according to Islamic rites.

• The Pirzada sect of Burhanpur revered the coming incarnation of Vishnu—Nishkalanki—while following Islamic teachings.

These examples show how composite Indian culture has been and that Islam in India developed not through isolation but through coexistence, dialogue, and adaptation.

Muslim women in Kashmir stitching national flag

Asim Roy, in his book Islamic Syncretic Tradition in Bengal, argues that Bengali Islam is not a diluted version of Arabian Islam, as some revivalists had claimed, but a valid historical evolution of the faith in a distinct cultural environment.

Rafiuddin Ahmed, another scholar similarly recognized a unique Bengali Muslim identity, as separate from North Indian Urdu-speaking Muslims.

Indian Muslims have never been a homogenous community. Islam in India grew through three streams—conquest, immigration, and conversion. Long before the advent of Delhi Sultanate and Mughals, Arab traders brought Islam peacefully to the Malabar Coast. The Cheraman Juma Mosque stands as a reminder of this early accommodation.

In North India, with the advent of Delhi Sultanat a distinct Perso-Islamic culture emerged. Yet when the ulema urged Iltutmish in 1285 to impose strict Sharia law, he refused—recognizing India’s diverse social fabric and even feared a stiff resistance from the native Indians. Yes, there were political excesses. But reducing Indian Islam to the Delhi Sultanate or Mughals alone would be a gross distortion.

The real expansion of Islam came from Sufi saints—who were individuals and did not represent any institution, especially the Chishtis—who embraced Wahdat-ul-Wajood, the oneness of all being philosophy. They settled among the rural poor, far from political power. They spoke the language of love, compassion, music, and poetry. Their khanqahs were centers of healing and harmony. Places where the natives enjoyed music and langars. In those placed they found relief from their sufferings.

P. Hardy in his book The Muslims of British India notes how Sufis were influenced by Indian yogic traditions, and how people found solace in their presence.

Later, philosophical debates emerged: Wahdat-ul-Wajud was challenged by the Naqshbandis, who advocated purification of Islam through Wahdat-ul-Shahud. Movements led by figures like Ahmad Sirhindi and later Shah Waliullah shaped nationalist Deobandi and Ahl-e-Hadis thought, though even these thoughts could not escape India’s powerful syncretic pull.

India also produced great thinkers and poets who strengthened its social fabric:

• Dara Shikoh translated the Upanishads and authored Majma-ul-Bahrain—the meeting of two seas.

• Amir Khusro gave us Khadi Boli, Hindavi literature, the tabla, and qawwali.

• Iqbal wrote a nazm on Lord Ram, calling him Imam-e-Hind. And wrote famous misra — kuch baat hai ki hasti mit tey nahi humari, sadiyon raha hai dushman dauren zaman hamara

• Ghalib penned Chirag-e-Dair in praise of Benaras.

• Hafiz Jallandhari and Hasrat Mohani celebrated Lord Krishna in poetry.

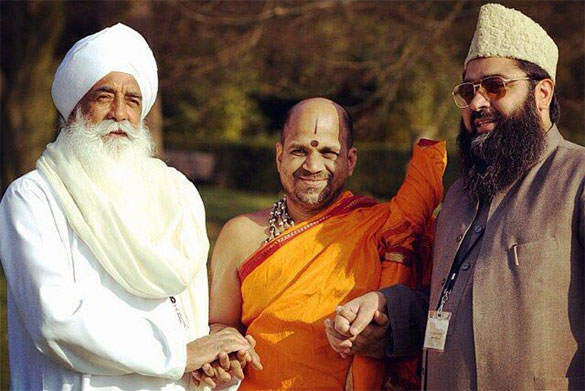

Religious leaders in the spirit of Sarva Dharma Sambhava

In Aligarh Sir Syed Ahmad Khan revolutionised education and introduced modern Muslim education. Great institutions—Darul Uloom, Nadwa—continue to evolve here because India has always offered intellectual freedom and space for spiritual growth.

Mushirul Hassan in the book Islam and Indian Nationalism quoting a British historian notes that Indian Muslims have failed respect and celebrate their heroes…hardly Indian Muslims visit the grave of Maulana Azad’s in front of Delhi’s Jama Masjid or that of Dr Zakir Hussain and M.A. Ansari.

Even scholars of Aligarh Muslim University have been insensitive to the ideological context provided by Aligarh movement with regards to the education, there is hardly any appreciation of the pioneering efforts of Syed Ahmed Khan. Though the movement was largely from the Ashraf point of view, but it did bring about revolution in Indian Muslim education.

Yet, it was colonial rule—especially toward the end—that struck the deepest blow to India’s inclusive ethos. The British enforced rigid identities—Hindu Vs. Muslim—weakening centuries-old shared values. And yes, even today, polarisation has grown globally and domestically. Influenced by post-9/11 Islamophobia and radical foreign ideologies, some Indian Muslims have dangerously drifted away from their indigenous, Sufi-inspired traditions.

David Lelyveld, a renowned sociologist in his book Aligarh’s First Generation, which primarily focusses on Muslim class differences says- the focus of British Colonial officers was on freezing identities and chopping off ambiguities in the Indian culture, eventually proving a mold for fixing Indian Hindu and Muslim identities.

Sadly, political mishandling post-Indian Partition of ignoring Hindu sentiments, and useless appeasement of Muslims for political gains has not done any good to this great country.

After the demolition of disputed structure in Ayodhya in 1992-Indian Muslim clergy lost their influence significantly- and Muslims aligned themselves with regional political aspirations. Even this did not help them in any way.

It’s no secret that our inclusive heritage has suffered setbacks. Despite having examples of great Muslims like A.P.J. Kalam and renowned archeologist K K Muhammad, who has done commendable scholarly work on 100 ancient temples in Bateshwar in Bundelkhand area, something has changed.

Today, the challenge before us is to reclaim that heritage—to revive justice, compassion, and the Sufi orientation that shaped Indian Islam. Indian Sufism also needs to do away with its corruption, which has set in.

There is a need for Indian Muslims to cherish their own Indian culture and not draw inspiration from the radicalized versions of Islam coming from foreign lands.

Thankfully, India continues to produce inspiring figures: Urdu poet Chandra Bhan Khayal, whose book Lolak contains Naat in praise of Prophet Muhammad; Muslims scholars world-wide are doing research on his work. Beetul Begum, a Rajasthani folk bhajan singer sings with such dedication that one could only praise her. We must ensure that such intellectual and spiritual traditions not only survive but thrive.

The political blunders of the past have led to accumulation of pressure and a strong Indian Hindus backlash, which is now in turn leading to consolidation of Indian Muslim identities—the biggest casualty of this phenomenon has been weakening of regional Muslim cultures identities. Bengali and Bihari Muslim women who for ages wore sari now prefer burqa; the dhoti of Muslim men in Bihar has all but disappeared. Cultural diversity among Muslims is shrinking.

When once renowned artist Vivan Sundaram was asked whether we could reduce chaos and Delhi could be made more orderly by making all colonies look alike. He said, “If all houses looked the same, it would be so boring. Beauty only lies in diversity.”

Neither Hindus nor Muslims in India alone are responsible for the challenges we face today. It is important to understand that the strength of India doesn’t lie in giving preference to any singular religious thought over the other. Those who ruled in the past understood this very well. We need to understand this now as well.

India as a nation stands on the delicate balance of plurality and not singularity.

India’s inclusive traditions—and its unique relationship with Islam—are not relics of history. They are the foundation on which a stronger, more confident, and harmonious India can rise.

ALSO READ: Mumtaz Khan's inspirational story as first TV professional from Mewat

Amid disruptions, we should remain hopeful. And see the possibility of a brighter future—one where we, as Indians, can think clearly, live fearlessly, prosper and collectively pursue harmony.

The author is Editor-in-Chief of Awaz-the Voice